Riff Raff: Finding an Arkansan to stand with Bates

by February 11, 2019 5:53 pm 746 views

His music was patriotic and subversive. He told us “The One On The Right Is On The Left.” He talked social justice for Native Americans and minorities and folks in our prison system. He stole a Cadillac one piece at a time.

The man who faced poverty, frequent rejection, marital problems, money problems and drug addiction would in the mid-1960s – at the beginning of his rise to fame – roll out the album “Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian,” with the discomforting song “Ballad of Ira Hayes.”

“Call him drunken Ira Hayes

He won’t answer anymore

Not the whiskey drinking Indian

Or the marine that went to war.”

A young, conservative, God-fearing Johnson County boy wondered years later when discovering Johnny Cash’s history why the Man in Black had to get political. Why couldn’t he just walk the line, you know, stick to singing? Country music leaders at the time also thought Cash should stick to music. DJs refused to play the new album and many refused to play his music altogether. There was a move to kick him out of the Country Music Association. He fired back. Doubled down. He let industry stalwarts know Bitter Tears was just one taste of “bitter medicine” the country needed to swallow.

“So is Rochester, Harlem, Birmingham and Vietnam,” he said of the other bitters.

He made it clear – even acceptable to that evolving Johnson County boy – that one could at the same time love and question our country and history. The same flag lifting the pride of a nation can cover up its crimes. Cash’s clarity of purpose would zenith in 1971 with “Man in Black.”

“Well, there’s things that never will be right I know,

And things need changin’ everywhere you go,

But ’til we start to make a move to make a few things right,

You’ll never see me wear a suit of white.”

When asked to perform in Nixon’s White House, Cash sang the Ira Hayes ballad, “Man in Black” or “What is Truth?” None were on the list of songs Nixon requested. Cash would later say he wasn’t familiar with the songs Nixon requested, but historians have noted Cash could have picked any number of songs to perform that weren’t so pointedly anti-war. When it came to what he thought was right, the military veteran who spent his formative years toiling in east Arkansas row crop fields and singing gospel songs would literally in the face of power walk the line.

Cash’s political history came to the fore recently as Arkansas legislators debated which two Arkansans should represent the state in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol. Statues of Arkansans U.M. Rose and James P. Clarke are now in the hall. (Google them.) Sen. Dave Wallace, R-Leachville, proposed civil rights legend Daisy Bates – solid choice – and Cash. A small contingent of Republicans approved of Bates, but not so much for Cash.

Roseanne Cash once called U.S. House Speaker and Republican John Boehner an “asshat” for using her dad’s name in a joke about President Obama. It probably doesn’t help that Roseanne and brother John Carter Cash are frequent critics of President Trump. Apart from the Cash family’s progressive political philosophy not always welcome in some Arkansas circles, the hit against Cash is he spent most of his life outside the state.

“I’ve got no problem with Johnny Cash, but I do have problem of putting a statue of him in our nation’s Capital. I can think of several people that have done more – that may have left their lives on some battlefield or something like that – than Johnny Cash,” Sen. Bill Sample, R-Hot Springs, said during a hearing on the issue.

Maybe Sam Walton, some said. Sen. Bart Hester, R-Cave Springs, seeks statues of Bates and Navy SEAL Adam Brown of Hot Springs who died in combat.

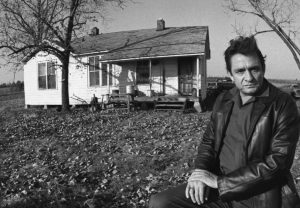

Ask the folks at Arkansas State University, the Dyess Colony – the New Deal town where Cash grew up in east Arkansas – and state tourism officials about Cash’s impact. The Johnny Cash Heritage Festival is coordinated by ASU and fully supported by the Cash family through the John R. Cash Revocable Trust. It grows bigger each year. The colony and its programs also annually attract a growing number of non-festival tourists.

But please know, Kind Reader, I’m not smart enough to know if Cash is the right choice. Am more than happy to defer to historians who know more about the rich characters of this wonderful state. Hell, picking two folks is nothing short of a Solomnic splitting of the baby.

What I do know is that Cash was imperfect. Real. Relatable. That’s his appeal to some. He’s a mix of talent, turmoil, empathy, and perseverance. He was a socio-economic mirror. He made us tap our toes while tapping our shared woes. He questioned authority. He showed us our collective failures, hypocrisies, opportunities, and successes around the myriad intersections of justice, politics, religion and just being human.

One may rightfully argue we didn’t need Cash for such lessons, but you can’t excise Cash from the lessons, and you can’t excise Cash from Arkansas.

And one may also rightfully argue for a statue in the nation’s Capitol to remind 535 folks “eatin’ in a fancy dining car … and smokin’ big cigars” that “things need changin’ everywhere you go.”