Former All-Star, Fort Smith native Jim King reflects on 10-year NBA career

by January 10, 2018 2:58 pm 5,233 views

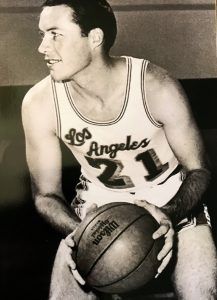

Jim King, while playing for the Los Angeles Lakers.

June 13, 2016. LeBron James and Kyrie Irving of the Cleveland Cavaliers score 41 points each to become the first teammates in NBA Finals history to put up more than 40 points in the same game. Fans wondered whether the pair’s 82 set an all-time scoring record as well, so they blasted ABC Sports with questions about past games to see if any others measured up.

Statisticians found out not only did the Irving-James connection fail to take the No. 1 slot — that place was held by the legendary scoring duo of Los Angeles Lakers standouts Jerry West and Elgin Baylor with 87 — it wasn’t even No. 2.

Jim King, 74 at the time (now 76), was watching when the graphic played during Game 6 the following evening, and his phone lit up.

“My phone was hot. I couldn’t get off of it. It just kept going. I probably had 20 calls,” King told Talk Business & Politics in a recent interview.

Now working in real estate part-time and living in the Dallas area near his children and grandchildren, the Fort Smith native once known as “Country” remembered what a treat it was for his family to see him pictured alongside Rick Barry in the number two position with 83 points between them. On the evening of April 18, 1967, the double-threat had been enough to vanquish the Philadelphia 76ers, led by seven-footer Wilt Chamberlain.

“You have to understand, my kids had never seen me play pro ball. They were too young. I have two daughters and a son, who is my oldest. He’s 51. When that came out, their friends started calling them from all over the world. Jim King! They all started getting their calls, and they were trying to call me because of it, but they couldn’t get me. I was on the phone, too. It was a really fun thing for them to see because people would always tell them, ‘You should have seen your dad play, he was really something,’ and they’d just say, ‘That’s what I hear.'”

UNDER THE RADAR

King wasn’t surprised it took a team of researchers to dig up that statistic. The game happened over 50 years ago, and he had a history of flying under the radar anyway.

“I was a Fort Smith, Arkansas, product, but I only had one offer to go to school, a major college anyway. We had eight seniors on our high school team, and all eight had offers to go to school somewhere. But I didn’t get the offer to go to Arkansas, so I took what I had in Tulsa. It wasn’t necessarily what I wanted, but it’s what presented itself. I wouldn’t have gone to college without it. But then people don’t see you as a local product any more once you go to college somewhere else, and then you’re not actually an Oklahoma product either because you’re from Arkansas.”

When the Los Angeles Lakers selected King in the 1963 NBA Draft, he was their second pick, which they had acquired from the lowly Cincinnati Royals in exchange for Tom Hawkins, a Notre Dame grad the team had taken in the 1959 Draft when they were still the Minneapolis Lakers.

Hawkins was an attractive prospect and despite the territorial nature of player selections, was undoubtedly on owner Bob Short’s radar. Short was a supporter of Notre Dame for several years, even up until his death in 1982, though he was a graduate of the College of St. Thomas and Georgetown University Law Center himself.

As the school’s first African-American basketball star, Hawkins enjoyed a 10-year run in the NBA before retiring in 1969 with 6,672 career points and 4,607 rebounds. Getting him was a no-brainer for a team languishing at the bottom of the then nine-team league, and Short already had his replacement in mind.

‘WHO THE HELL IS JIM KING?’

The Drafts in those days weren’t the lavish ESPN-televised affairs you see today. They were little more than a conference call among owners and general managers, and when Short got his chance to use the newly acquired pick, he didn’t think twice. His GM had been receiving news clippings about a University of Tulsa player, sent by a student to his father, who was the consultant Short used when relocating the team from Minneapolis to L.A. Short saw potential in King, and when selection time came, he said, “We’ll take Jim King from Tulsa.”

The other owners had a pretty immediate reaction, and it was less than flattering: “Who the hell is Jim King from Tulsa?” Short responded simply, “It’s my damn team. I’ll take whoever I want.”

King would become the 13th overall pick (14th if you count the “territorial pick” the Royals received prior to Round 1). For sake of comparison, the 2017 NBA Draft’s 13th and 14th picks — Donovan Mitchell and Bam Adebayo, respectively — are estimated by Forbes to earn $5.732 million and $5.446 million for two-year contracts.

King laughs about the comparison, telling Talk Business & Politics his selection was “wrong timing.” His own starting pay was $9,500 with a $500 bonus, though it did go up every year he stayed in the league, and significantly when the American Basketball Association (ABA) arrived on scene pre-merger. The ABA paid talent more money and forced the NBA’s hand to do the same. But to year one totals, $10,000 in 1963 would be worth about $80,000 today — a far cry from Mitchell and Adebayo money.

That said, King was determined to make the most of his opportunity. He tried (and failed) to get a “no-cut contract,” which is a contract guaranteeing an athlete will remain on roster for a specified time. But setback aside, the GM promised he would get “an equal chance” to make the team.

“If you can bring the ball down the floor and get it to Jerry (West) and Elgin (Baylor), you can make this team probably, but if you can cover the best offensive player on the other team, it’s a done deal,” King was told. “I said, ‘I can do that.'”

BAYLOR AND WEST

Baylor and West, both Hall of Famers, were already a feared scoring combination when King got his tryout. West — the player pictured in the NBA’s iconic logo — was known as “Mr. Clutch” for being able to hit shots in high-pressure situations. As King remembers him, “He might miss the first three quarters, but the fourth quarter, I can promise you, he’d be on.”

As for Baylor, “He could do everything.”

“I saw him slam it over (Bill) Russell one night” — whom King calls the best he ever played against. “His left foot was on the free throw line. He was flying through the air. He took his left hand and just moved Russell over, slammed it right over him.” Baylor also was the first player to break the individual 70-point barrier for scoring in one game.

“And he could handle the ball really well. I mean, you had to keep your eye on him if he had the ball, because sometimes it would hit you in the face or hit you in the chest, and you’d be like, ‘Where did it come from?’ He could pass through people. He just really knew how to play the game. You’d try to cover him, and he would invent a shot.”

Because of that, King’s job as point-guard was simple. “I didn’t have to worry about scoring. I thought, ‘I know I can score,’ but I went out there with the idea of playing defense and handling the ball and that kind of stuff so Jerry didn’t have to, because everything was because, ‘So Jerry doesn’t have to.’ They didn’t want to get him in foul trouble because he was so valuable down the stretch. He would win 25 games a year by taking over the last eight minutes.”

King’s admiration for West extended beyond the court. In fact, he credits the NBA legend for giving him a break that would lead to his own 10-year run in the league.

TULSA TO L.A.

It was open camp, and King’s draft selection in no way meant he would make the team. Fresh from college graduation, he had to first decide whether the trip was even worth it. Many of his athletic peers were drawn by the promise of “industrial league” jobs in which they would play as amateurs for company teams like Phillips 66 and Denver Truckers with the promise of a regular job out-of-season and after retirement. Following through on the NBA tryout would forever remove King’s amateur status, rendering him ineligible for the security of such leagues.

“I had an offer, and I’ll admit I was tempted, but I would have had to live with, ‘I wonder if I could have made it.'”

King went.

His August trip from Tulsa to Los Angeles didn’t have the benefit of expressways.

“It was all (Route) 66,” he remembers, adding that it was a trip he would have to make in a 1955 Ford with no air conditioner that had until recently been trailing plumes of smoke.

“One of my wife’s (then fiancee’s) brothers had a friend. His dad was a stock car racer, and he was one of the mechanics. He was at their house one day and saw me start it up. Smoke flew out the back, and he said, ‘Man, you need a ring job,’ and I said, ‘Yeah, where can I get it?'” The friend’s quote of $125 was accepted and the procedure, which entailed disassembly of the engine and removal and replacement of piston rings, readied King for the 1,400-mile journey.

With about half his bonus left — he used $130 to buy an engagement ring that has paid off in a marriage 54 years strong — King set out for the West Coast, driving at night and careful not to hit the long desert stretches during the day. He hoped the Lakers would allow him to come in early, “but they said, ‘No, you get here on Sunday like everybody else.'”

‘EQUAL CHANCE’

King complied. When he arrived, he met 6’5″ first-round draft pick Roger Strickland and found out Strickland had been working with the team for about a month.

“So I knew everything was equal, right? I got an equal chance,” he joked. “So I go to practice the next morning, and I’m ready to kill somebody.”

King shook the feeling and accepted the challenge, commencing drills, which high school coach Gayle Kaundart had impressed upon him early and often.

Lakers’ coaches “wanted to see if the guys could run and how much they’d been coached — see how their fundamentals were.” When drills began, it was a “disaster,” with collisions, players getting hurt and losing the ball. “Just a disaster,” King said.

King was then asked to lead the drills, and “Every drill he mentioned was one of Coach Kaundart’s drills. But Coach Kaundart wanted them done left-handed and right-handed and full speed. That’s the only way you do them. ‘Otherwise you go down there and practice until you can play with the big boys,’ he’d say. So I knew how to do them right, and that moved me up.”

‘ONLY ONE GUY CAN MAKE US BETTER’

Camp was at the Loyola Marymount University gym, and King remembers it as sweltering.

“We worked for the first hour, and about 30 minutes into it, they opened the side windows because there’s no air conditioning in there. Well, the smog just rolled right into the gym. You could not get a deep breath. We were all dying. That first 30 minutes, coach said something to the number one draft pick (Strickland), and he smarted back to him, and coach said, ‘Son, right there’s the door. You can turn your stuff in. You’re through.'”

King continued: “So he didn’t last 30 minutes. I thought that was negative they brought him in 30 days early, but it was a positive because they saw he couldn’t play. He led the nation in scoring two years in a row, but he couldn’t do anything else. All he could do was shoot. Well, they told me they didn’t need shooters. They needed someone who could bring the ball down and get it to the shooters. West and Baylor were averaging about 70 points between them, so they didn’t feel like they needed that much help.”

With just seven hopefuls left, the next 30 minutes wrapped up. When the whistle blew, the coach told everyone to take five and grab a drink of water. Six of the men dropped to the floor. King did not. “I couldn’t go to the floor. I never had a coach — Kaundart especially — who would let you sit down in practice, and my college coach was the same way. Nor did you get drinks of water.”

Falling back on the training he received at Fort Smith High School, King ran to the other end of the court, grabbed a ball, and began shooting free throws and doing ball handling drills. He didn’t know it at the time, but Jerry West was sitting in the stands watching. West leaned over to the GM and said, “There’s only one guy here that can make us better.” He pointed to King. “That kid right there.”

KAUNDART

When King joined Coach Kaundart’s team at Fort Smith High School, he had never watched professional basketball, thinking of himself more as a baseball player. The thought of making a career in the NBA was nowhere on his radar. But as friend and former teammate Tommy Boyer remembers, Kaundart was the kind of coach who “took an average player and made them good, and he took a good player and made them great. Jim was great.”

Similar to Michael Jordan’s humble beginnings, King didn’t start out as a superstar. Actually he didn’t start, period. He was the “sixth or seventh” man on his high school team, but over one summer grew two inches and put on 15 pounds while mastering Kaundart’s fundamentals. By his senior year, he was All-State, and while the University of Arkansas saw him as too small and too slow — Kaundart fumed about that, “What do you want, a basketball player or a track star?” — he found success at the University of Tulsa where he was two-time first team All Missouri Valley Conference.

When Kaundart died in November 1995, he left behind an impressive career that included 11 state championships and, at the collegiate level, the 1981 national title with Westark College. Most of Kaundart’s reputation, however, was in high school where he spent 24 years as a coach and led Fort Smith Northside to a state championship with a 30-0 record in his final season (1973-74). Kaundart “was a great coach. He was a legend,” King remembers. “I had a lot of college and pro coaches, and no one could touch him.”

Of course, Kaundart only provided the training. To get to the NBA, stay in the league 10 years, and play in an All-Star game (1968), King had to have talent and execute. He knows this, but he is often self-deprecating and passes credit along when talking about his career. When Boyer, now one of the 10-person board of trustees for the University of Arkansas System, brags about how well King played against NBA Champion, MVP, and 12-time All-Star Oscar Robertson, King shrugs off the praise and says, “I had to cover him a lot. You don’t stop him. You don’t just go out there and stop him like you do a lot of them. So I played him well a couple of times, but it was usually because he had a bad night, and he missed more shots than he normally did.”

King also shares deep admiration for former teammates and rivals like West, Baylor, Nate Thurmond (“I loved Nate”), Rick Barry (a “prima donna,” but a great player and someone with whom he “got along well”), Chet Walker, Jerry Sloan, Al Attles, Rudy LaRusso, Bob Love, and Jeff Mullins, to name a few.

Of Chamberlain, he remembers a giant of a man who “didn’t know how strong he was.” Someone who brought the ball through the hoop with such force that it dinged off King’s head and flew into the stands on one occasion and on another lifted him off the ground as King held on with both hands for the jumpball. (“I’m thinking, ‘Does he even know I’m on here?'”)

STAYING POWER

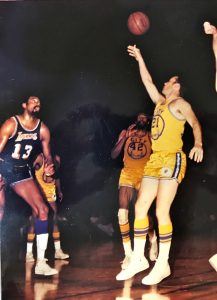

“It was great to be able to play with them,” King says, but King didn’t just “play with them,” he belonged with them, making the playoffs nine of his 10 seasons. He spent four years as an integral part of the L.A. Lakers. He and Barry achieved their historic scoring feat as San Francisco Warriors (now Golden State). He also played for the Cincinnati Royals (now Sacramento Kings) and helped pioneer the newly minted Chicago Bulls franchise for the last three years of his playing career.

Considering the number of top talents who burn out each year in professional sports, being able to play for as long as King did — and to be able to leave on his own terms in an era stacked with talent — speaks for itself. When asked how he was able to do it: “The big thing was to be consistent. A lot of guys come out, and they’re just a flash in the pan. But when you play in a playoff game, where you’re playing five games in a row or seven games in a row, and you’re playing the same team every night or every other night you play, you have to be a cerebral player. You can’t just go out there and go through your motions and think, ‘I can do the same thing every night,’ because they’ll switch somebody else and put them on you and what you thought you were going to do, you won’t be able to do. You’ve got to do something else. You’ve got to go left instead of right. If you’re left-handed and they offer you the right and you don’t want to take it, you’re restricted because they’re going to cover your left. Just stuff like that. You learn to think and use your head a little more. You have to, or they’ll figure you out.”

By the time King retired from Chicago to coach Athletes in Action and, later, the University of Tulsa, he had scored 4,377 points, snagged 1,500 rebounds, and made 1,412 assists. He also had earned the respect of the men he had played with and against. Many, including West, even appeared at his Mannford, Okla., basketball camp the final year of King’s playing career (1973).

His only regret: “I wish it was like golf where you could keep playing.”

In the meantime, he is content to duel it out with his grandson on the free-throw line. In fact, shortly after the boy’s 18th birthday, they had a shootout. King led through much of it, but by the end — “we must have shot 70,” he says — he fell just short. “When it was over, I was glad,” King said. “I hate to lose, but it was a big deal to him.”