Filmmakers reflect on long-term effects of Japanese internment

by May 9, 2017 5:34 pm 1,415 views

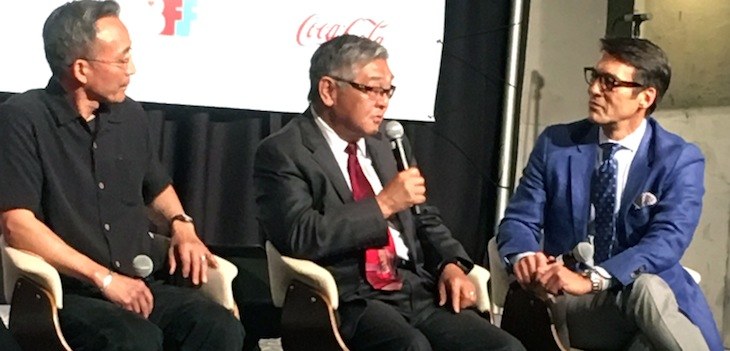

(from left) Two descendants of Japanese detainees, Maryland native Paul Takemoto and Arkansas native Richard Yada, along with Los Angeles television co-anchor David Ono spoke May 5 at the Bentonville Film Festival.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order in February 1942 that authorized the military to – in designated areas on the West Coast – force out individuals deemed to be a threat to national security and detain them at remote, government-run facilities.

Issued during World War II, just three months after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, the measure was meant to be a “protection against espionage,” according to the order. It resulted in more than 100,000 men, women and children of Japanese descent being moved to 11 internment camps, including two located in southeast Arkansas.

Seventy-five years later, the families of those incarcerated at the camps still feel the effects of the forced relocation, said filmmaker Vivienne Schiffer. That is the subject of a documentary she produced and co-directed, “Relocation, Arkansas – Aftermath of Incarceration.”

It features stories surrounding former detainees of Arkansas’ two Japanese internment camps, the Jerome and Rohwer war relocation centers. Each opened in the fall of 1942, and estimates show they collectively housed about 15,000 individuals, mostly from California, before the Jerome center closed in June 1944 and the Rohwer center closed in November 1945. (See the movie trailer at the end of this story.)

“Relocation, Arkansas” was shown as part of the Bentonville Film Festival on May 5 at The Record in downtown Bentonville. A panel discussion followed, led by ABC7 News Los Angeles co-anchor David Ono and featuring two descendants of detainees, Maryland native Paul Takemoto and Arkansas native Richard Yada, in addition to Schiffer and her mother, former McGehee Mayor Rosalie Gould.

Ono said he, as a Japanese American, was not aware for many years of the history of internment camps in the country.

“They don’t teach this enough in our schools,” Ono said. “We don’t talk about this chapter in our history enough.”

Takemoto, Yada and Gould all are featured in “Relocation, Arkansas.” Takemoto said he used to be “willfully ignorant” about his family’s history and was “ashamed to be Japanese American” for much of his life. However, his feelings changed after visiting the Arkansas site where his mother and grandparents were forced to live, he said. He credits Gould and Schiffer for playing roles in his realization of the importance of his family’s history.

REMEMBERING ROHWER

Gould served as mayor of McGehee from 1983 to 1995, and during that time she championed the cause of honoring former internment camp detainees, despite receiving hate mail and death threats when she suggested turning an empty train depot into a museum about internment camps, according to the film.

When former detainees and their families visited to dedicate a third monument at the Rohwer center, Gould agreed to host a dinner for the group at her home. Since then, she has hosted hundreds of former detainees and their families to dinner and shown them to the sites at Rohwer and Jerome.

A former art teacher at the camps gave Gould an assortment of artwork created by the detainees during the war, and through the years visiting family members added to her collection. Gould has since donated more than 100 pieces to the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, a department of the Central Arkansas Library System. In addition to the artwork, the collection contains original documents, including 180 autobiographies written by 12th-grade detainees.

She praised the art collection: “The Japanese community can take anything that’s ugly and turn it into beauty,” whether it is scrap wood or cypress knees, Gould said.

Schiffer now lives in Houston, but grew up near the Arkansas internment camps, which she learned about, in part, from her mother.

“What really fascinated me about it was this concept that people had come from somewhere else to Desha County, Arkansas, against their will. What did they feel? What did they think?” Schiffer said.

Over the course of 30 years or so, she listened to the stories and researched the camps, leading her in 2013 to publish a fictional book, “Camp Nine,” set in the Rohwer incarceration camp.

JAPANESE AMERICANS IN RURAL ARKANSAS

Yada was born in the Rohwer Camp. His parents opted not to return to their home in California following their release from internment and instead stayed in Arkansas, where they made a living as sharecroppers.

Yada, now managing director at National College Planning and certified financial planner at LPL Financial in Little Rock, described in the film his experience being dropped into a rural Arkansas town with deep racial division between blacks and whites, who drank from different water fountains, attended different schools and who were not permitted to frequent the same establishments.

“Relocation, Arkansas” features how Japanese Americans fit into the racial climate during the 1950s, including the onset of integration in public schools.

Yada said the Japanese American newcomers were embraced by the white community. He recalled, for example, his first-grade teacher taking him to the state fair while his parents were preoccupied with farm work.

He served in the U.S. Air Force after graduating college at the University of Arkansas in the early 1960s, and he is forgiving about the subjugation his family faced in the 1940s.

“People run democracies, and people make mistakes,” Yada said.