A century of death: 196 executions, 15 governors, and Arkansas’ deadliest day

by April 1, 2017 1:01 pm 3,828 views

On July 25, 1902, Arkansas sent six men to the gallows — Lathe Hembree, Dee Noland, Tom Simms, Dave McWhirter, Jim Johnson, and Cy Tanner, or, as the July 26 edition of the Arkansas Gazette put it, “four negroes and two white men.”

Almost 115 years later, the state of Arkansas has planned eight executions over a 10-day period in April marking an end to a 12-year dormancy brought on in part by a 2012 Arkansas Supreme Court decision that ruled the death penalty unconstitutional as currently practiced. Lawmakers have since worked out the kinks, and death row prisoners Don Davis and Bruce Ward will face lethal injection — the state’s method of execution — on April 17.

Robert Dunham, executive director of the Washington, D.C.-based Death Penalty Information Center, recently told Talk Business & Politics the volume of planned executions are “unprecedented” in the modern era. He isn’t wrong when you distinguish what the “modern era” is. But the rapid administration of sentences now less than one month away is hardly unprecedented when looking at Arkansas’ capital punishment history.

The July 25, 1902 executions were carried out in the cities of Washington, Chester Point, Arkansas City, Forrest City, and Van Buren, according to the Arkansas Gazette, which was obtained from Arkansas State Archives in Little Rock. Lauren Jarvis, archival manager for public services at the agency, could not verify whether the day was the deadliest in the state’s capital punishment history as “we do not have a comprehensive list of executions prior to 1913” and she did not know “of another department that has created a comprehensive list for this time period.”

The Archive’s records end in 1964 while the Death Penalty Information Center has information from 1977 forward. The Arkansas Department of Corrections also has a listing that combines the two along with current death row inmates, but it does not have anything prior to when the so-called “modern era” of when executions began. There are lists of executions in Arkansas online that date back to 1901, “but there is not a lot of information” provided on the websites, and “I cannot vouch for the accuracy of the data,” Jarvis said. (For example, The Death Penalty USA website shows seven hangings on July 25, 1902, with James Kitts, a black man convicted of murder, also hanged in Desha County.)

DEFINING THE ‘MODERN ERA’

Arkansas has endorsed the death penalty for the better part of 200 years. Incorporated as a state in 1836, executions were already present during the American Revolution with several members of the garrison at Arkansas Post convicted of having plotted on behalf of the English to massacre all soldiers stationed there. The conspirators were executed by firing squad on an undisclosed date in New Orleans.

For several decades prior to the modern era (which began in 1913), executions were carried out in the counties where the crimes occurred. Fort Smith-based “Hangin'” Judge Isaac Parker, who ruled as a federal judge for the Western District of Arkansas starting in 1875, was one of the most prolific facilitators of the death penalty, sentencing 160 to death during his tenure. About half (79) were carried out. The old way continued with brief overlaps to the modern era. The last to be executed in the county system was John Arthur Tillman for killing his girlfriend, tossing her in a well, and trying to conceal her body with stones. He was hanged at the Paris jail in Logan County on July 15, 1914.

For several decades prior to the modern era (which began in 1913), executions were carried out in the counties where the crimes occurred. Fort Smith-based “Hangin'” Judge Isaac Parker, who ruled as a federal judge for the Western District of Arkansas starting in 1875, was one of the most prolific facilitators of the death penalty, sentencing 160 to death during his tenure. About half (79) were carried out. The old way continued with brief overlaps to the modern era. The last to be executed in the county system was John Arthur Tillman for killing his girlfriend, tossing her in a well, and trying to conceal her body with stones. He was hanged at the Paris jail in Logan County on July 15, 1914.

The end of this system was brought on by the Arkansas General Assembly. Disturbed by the high death rates associated with convict labor, lawmakers began a penitentiary reform effort that would, among other things, centralize executions at the State Penitentiary in Little Rock. On Sept. 9, 1913, a 21-year-old black male named Lee Sims — the first under the modern death row system — was executed for the crime of rape. He was also the first to die in the electric chair and was followed there on Dec. 12 of that year by another black male, 19-year-old Ed King. With few exceptions, the electric chair would be the state’s official method of execution until 1990.

A TURBULENT START

The paradigm shift for how the death penalty is administered in Arkansas began with turmoil at the top. In 1912, Arkansas Gov. Joseph Taylor Robinson was elected as No. 23 in the state’s history. He would have presided over the first centralized execution if not for the death of U.S. Sen. Jefferson Davis on Jan. 3.

Davis had been reelected by the legislature for a term to begin on March 4, 1913. His death left a vacancy Robinson was eager to accept. On Jan. 27, 1913, only 12 days after taking the oath of office as governor, Robinson was elected to the post by lawmakers. He would serve as governor until the Senate term began, after which farmer William Kavanaugh Oldham would take over as acting governor for six days.

When the legislative session closed on March 13, the Arkansas Senate elected Junius Marion Futrell as the new president pro tempore, but Oldham refused to acknowledge Futrell’s right as acting governor. The Arkansas Supreme Court would decide in favor of Futrell two weeks later on March 24. Even after this decision, turnover was incomplete.

Futrell served only five months as acting governor thanks to a special election that slid George Washington Hays into the post on Aug. 6. The special election made Hays No. 24 and set him up as the first governor to preside over the new death penalty model. During his one term, nine prisoners were put to death — two rapists and seven murderers.

Gov. Charles Hillman Brough took over after him from Jan. 10, 1917 to Jan. 11, 1921. Brough racked up another eight executions and was followed by Gov. Thomas Chipman McRae. Under McRae, the state execution business really picked up. In one four-year term, the Democrat had 14 men executed, all for the crime of murder. He was also a rare Equal Opportunity death warrant issuer when it came to race, issuing an even mix of seven for whites and seven for blacks.

DEATH PENALTY BY RACE

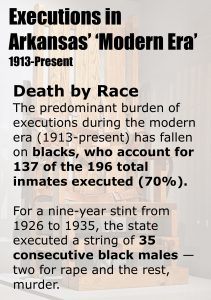

After launching the modern era with Sims and King, the state would execute two more black males for the crimes of rape and murder the following year before executing 19-year-old Arthur Hodges on Dec. 18, 1914. Hodges would become the first white person to receive the punishment and one of only 57 (29%) in the 104-year history of the modern system.

The predominant burden of executions during that same tenure has fallen on blacks, who account for 137 of the 196 total inmates executed (70%). For a nine-year stint from 1926 to 1935, the state executed a string of 35 consecutive black males — two for rape and the rest, murder.

The predominant burden of executions during that same tenure has fallen on blacks, who account for 137 of the 196 total inmates executed (70%). For a nine-year stint from 1926 to 1935, the state executed a string of 35 consecutive black males — two for rape and the rest, murder.

This lopsided spree of executions began with Gov. Tom Jefferson Terral, whose two-year term began in January 1925. Despite his abbreviated time in office, he managed to authorize a total of 13 executions. Gov. John Ellis Martineau ramped this down considerably with only three executions, though he did not serve out his full term and left office on March 2, 1928, after being named president of the Tri-State Flood Commission. This was in response to the Mississippi River breaking free of its banks and covering over 13% of the state during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927.

Martineau’s lieutenant governor, Harvey Parnell, followed him, serving from March 2, 1928 to Jan. 10, 1933. Parnell was the busiest governor to date when it came to signing death warrants. His tenure in office enabled the executions of 17 men, all of whom were African-American, making up about half of the 35-kill streak. The final seven would occur under Gov. Futrell, who was elected to two terms starting in January 1933 after his prior stint as acting governor.

Futrell’s tenure was the most prolific to date with 21 executions. The run closed with the deaths of three black males from Drew County who were convicted of a homicide and killed on the same day of Dec. 11, 1936, which remains one of the five deadliest days in the modern era just behind Feb. 12, 1926, and Nov. 14, 1930 — dates on which four black males were executed on the same day.

DEATH PENALTY DECLINE

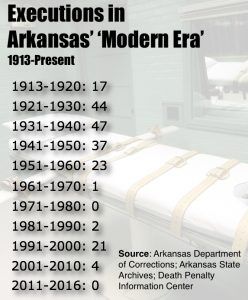

For many years, there was a decline in use of the death penalty in Arkansas. While influenced by the controversial 5-4 Furman v. Georgia decision, the state had largely curtailed the practice on its own. After putting eight men to death in 1960 and one in 1964, it would go on its longest dormancy period in history. Before 1960, a year seldom went by without Arkansas executing one or more inmates.

This started to change with Gov. Francis Cherry, who took office on Jan. 13, 1953, and would serve only two years. He was the first since Martineau to serve two years or less. Until Cherry’s tenure, Martineau held the distinction among Arkansas governors who issued death warrants as being the one with the least amount of executions for the modern era at three. Cherry beat this by overseeing the execution of only one prisoner — a 50-year-old Native-American man from Garland County named Bill Jenkins for the crime of murder — before losing a runoff election to eventual six-term Gov. Orval Faubus.

Gov. Faubus was elected to his first term in 1954. Seeing that Faubus was the longest-serving governor in the state’s history with 12 years in office, one might think him to be the most prolific warrant issuer. However, his administration would oversee the executions of only 16 men, or barely one each year, and he would also perform the last execution – Charles Fields in 1964 – prior to the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark decision.

Faubus screeched the brakes of the death penalty after a busy 1959 and 1960, during which 14 of his 16 warrants were carried out. Fields would be the only execution from 1960 until Faubus left office in 1967, and he was the last until former governor and 42nd President of the United States Bill Clinton resumed its use in 1990.

Arkansas initially carried out executions on murderers and rapists. This practice would remain legal until another U.S. Supreme Court decision – Coker v. Georgia (1976) – ruled the death penalty was a disproportionate punishment for the crime of raping an adult woman and was therefore in violation of the Eighth Amendment. Fields was the last rapist to be executed in Arkansas and one of 21 rapists in the state’s modern era.

EXECUTIONS, 1990-PRESENT

Arkansas’ interest in the death penalty resumed on June 18, 1990. A comparatively busy execution schedule – at least compared to the previous 26 years – resumed with the death of John Swindler, who was the first prisoner to be convicted for the crime of capital murder, or any murder that made a perpetrator eligible for the death penalty. Each of the 26 prisoners executed after Swindler, and all 34 of inmates now on Arkansas’ death row carry the same distinction.

With Swindler’s death – the last to be administered using the electric chair – then-Gov. Clinton oversaw two executions, but signed a third controversial warrant in the case of mentally impaired murderer Ricky Ray Rector. Less than a month after taking the oath of office as President, Clinton would return to the state during Rector’s execution, which officially occurred during Gov. Jim Guy Tucker’s four years in office.

Clinton has received criticism in more liberal circles for allowing the execution of Rector to go forth as the convicted had shot himself in the head in a suicide attempt after killing a man in a nightclub and then shooting and killing Conway Police Officer Robert Martin in the aftermath. The resulting gunshot wound effectively lobotomized Rector, who famously ordered pecan pie as part of his last meal, then refused to eat it telling corrections officers he was “saving it for later.”

Political opponents, who ordinarily wouldn’t have opposed the death penalty, also criticized Clinton’s return to Arkansas as a political move meant to invoke the image of a leader tough on crime.

The circumstances of the case are noteworthy because after the death penalty resumed in the U.S. and, subsequently, Arkansas, appeals processes grew lengthier and more complex, bringing forth the valid question of which governor would get “credit” for an execution.

For simplification, the 1990-present totals break down as such: Gov. Clinton (2, with an asterisk by Rector), Gov. Tucker (9, same asterisk); and Gov. Mike Huckabee (16 during his 10-plus years in office from July 15, 1996-Jan. 9, 2007). Huckabee also holds the distinction of being the only Republican governor to oversee one or more executions. The remaining 180 were signed off on by a total of 14 Democratic governors. Former Arkansas Gov. Mike Beebe, a Democrat, said prior to leaving office he would have signed a law banning the death penalty outright. That said, he issued four death warrants yet to be carried out.

The most recent inmate to be executed was 45-year-old convicted murderer Eric Nance on Nov. 29, 2005.

The death penalty was temporarily suspended by the Arkansas Supreme Court on June 22, 2012, after justices ruled then-current execution law was unconstitutional because it allowed the executive branch to decide on some execution issues which were under the purview of the legislature.

Link here for a PDF of a list of executions since 1913. The table features the names, races, genders, ages, crimes, and dates of executions of each inmate by governor as reported by the Arkansas Department of Corrections and compiled by Talk Business & Politics.