Fort Smith’s bicentennial heritage

by December 23, 2015 10:05 am 453 views

guest commentary by Daniel Maher

Editor’s note: This commentary is part of a collaboration between the University of Arkansas at Fort Smith and Talk Business & Politics to deliver an ongoing series of political-based essays and reports. Daniel Maher is the assistant professor of Anthropology and Sociology at the University of Arkansas at Fort Smith. His published works are “Vice in the Veil of Justice: Embedding Race and Gender in Frontier Tourism” (University of Arkansas, 2013) and “Mythic Frontiers: Remembering, Forgetting, and Profiting with Cultural Heritage Tourism” (University Press of Florida, 2016 estimated). He can be reached at [email protected]

Opinions, commentary and other essays posted in this space are wholly the view of the author(s). They may not represent the opinion of the owners of Talk Business & Politics or the administration of the University of Arkansas at Fort Smith.

––––––––––––––

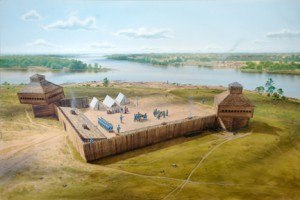

Though the bicentennial of the founding of the city of Fort Smith is in 2042, plans are well underway to commemorate the arrival of federal troops to Belle Point in December of 1817 in what was then part of the Territory of Missouri.

Arkansas Territory, including the modern states of Oklahoma and Arkansas was carved out in 1819, Arkansas statehood came in 1836, and John Rogers led the incorporation of the city in 1842.

The way in which we remember the establishment and presence of the 1817-1824, and then 1838-1871 military forts in heritage narratives, is at variance with a more rigorous historical rendering of the period. The Fort Smith National Historic Site “Orientation Video” projects the archetypal narrative of the establishment of the military fort in its very title – “Fort Smith: The Peacekeeper of Indian Territory.” The video begins: “Fort Smith, it’s the window through which you see the history of the vast panorama of the west unfolding. This military outpost acted as a funnel, feeding into the wilderness soldiers, traders, explorers, emigrating Indians, and settlers. They came here first before heading out to their western destinations.”

The take-away from this master-narrative is that the fort was put here to “keep the peace between the Indians.” That same narrative extends through the federal court era, 1871-1896 and I have critiqued that period in a previous commentary. The orientation video adamantly declares: “And for nearly eighty years Fort Smith’s presence served notice to the lawless that the full and complete authority of the United States government stood on the frontier.” This clearly stated Genesis account begins time in Fort Smith with the arrival of the United States government.

That the first fort was abandoned in 1824 and replaced with Fort Gibson belies the larger reason for the presence of the fort. In “Fort Smith: Vanguard of Western Frontier History Southwest,” Billy Higgins notes that the fort was just one in “a chain of fortifications along the length of the western frontier of the United States, each one of them garrisoned by a single company of the U.S. Army’s Rifle Regiment. These frontier posts formed the young nation’s line of defense on its western borders and stretched from Green Bay on the Fox River in Wisconsin to Fort Claiborne on the Red River.”

More pointedly, “Fort Smith: Little Gibraltar on the Arkansas,” by Edwin Bearss and Arrell Gibson, opens with, “the United States Army was a primary force in opening the Southwestern wilderness. By 1817, a pattern of military settlement had developed which was repeated with increasing regularity.” It continues, “When the area was safe for pioneer farmers and townsmen the soldiers moved on to open new frontiers.” Rather than protecting Indians, Bearss and Gibson emphasize, “the most obvious duty was military—guarding the United States when the Southwest was shared with Spain and Mexico.” As a side effect, “an extension of the military role was pacifying the Indian tribes upon whose hunting range the military settlement intruded.”

“Keeping the peace between the Indians” turns out to be a euphemism for “the United States government and its citizens are here to take this land away from you.”

Closer scrutiny of the details makes the “keeping the peace” narrative preposterous.

Higgins notes there is scant evidence that the military was used to encroach into Indian-versus-Indian affairs. On the contrary, “(Major) Bradford never ordered his rifle company into the field to head off or to punish the Cherokee or Osage raiders in Arkansas or in the territories to the west.” This was the stance despite direct pleas on the part of Indians and other representatives to establish peace between the Cherokee and the Osage. Higgins asserts: “Bradford’s actions cast doubt on the standard historical interpretation that Fort Smith was founded for the purpose of keeping peace between the Indians. That does not seem to be the role that the commanding officer understood for himself and his garrison once it was established. Bradford intended to use force against Indians only when they attacked whites on non-Indian territories.”

In “The Native Ground,” Kathleen DuVal notes that: “Federal officials had no qualms about intervening when Indian warfare endangered whites. … Official policy on the Osage-Cherokee war stated that ‘the U. States will take no part in their quarrel; but if, in carrying on the War, either party commit outrages upon the persons or property of our citizens,’ Major Bradford’s troops should act.” In response to spreading rumors that Osage and Cherokee were about to cause violence to whites, Bradford, quoted in Du-Val, promptly and sternly laid down the power of the federal government: “‘if you shed one single drop of a White man’s blood I will exterminate the Nation that does it,’ leaving ‘not a Cherokee or Osage alive on this Side of the Mississippi.’” The peace was thus kept by allowing Indians to kill each other and by threatening to kill any Indians who interfered with white intrusion into the region.

Why was the first fort built? What is the upcoming bicentennial commemorating? At minimum it is clear that it was not to keep peace between Indians but rather to create a stable place to relocate Indians from the Southeast in order to open up more agricultural land for whites in Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi.

But, why was a second fort built in 1838?

Fort Smith’s relation to Indian Territory was always more nuanced than tourist narratives in the frontier complex reflect. In 1833, when Captain Stuart was doing battle with John Rogers over whether a second military Fort Smith should be constructed, Bearss and Gibson document that Stuart aired a candid and prescient comment regarding the Fort Smith–Indian Territory border: “If Troops are ever Stationed in this Territory, for the avowed purpose of giving protection of the White inhabitants against the neighbouring Indians, difficulties and contentions will at once arise between the two parties. The depraved portion of the Whites, feeling themselves Protected by the Military will commence their Lawless outrages on the Indians, by Killing and Stealing their property and often molesting their person.” But, John Rogers had significant personal reasons for wanting the establishment of a second Fort Smith. He had been investing in and developing hundreds of acres surrounding the first fort for nearly two decades and wanted a return on his efforts.

Construction on the second Fort Smith began in 1838 over loud protestations by many in the military. Completed in 1846 it was permanently closed by President Zachary Taylor four years later. Had it not been for Taylor’s death shortly after, Fort Smith may have never been reopened. Taylor resided in Fort Smith from 1842-1845 and made his opinion on the construction of the second fort quite clear. Bearss and Gibson relay that, “Taylor established his headquarters at Cantonment Belknap (about a mile east of the fort) … and was thus close to the Fort Smith situation and could observe it at first hand. Taylor … was shocked at what he regarded useless expenditure of public funds at Fort Smith.” He said that “when finished it would ‘serve as a lasting monument to the folly of those who planned [it], as well as him who executed [it].’”

In a personal letter, Bearss and Gibson found that Taylor’s opinion of the second fort was unambiguous: “The plan … is highly objectionable. … A more useless expenditure of money & labor was never made by this or any other people. … The sooner it is arrested the better.” The combination of the death of President Taylor and the political acumen of John Rogers saved military Fort Smith and established a long tradition of the local economy being propped up with federal dollars.

Yes, I believe we should definitely commemorate the upcoming bicentennial, and do so with as accurate of an image of the city’s origins as is possible. Behind the heritage narratives of Fort Smith lie the spoils of Manifest Destiny of our nation, and of John Rogers.