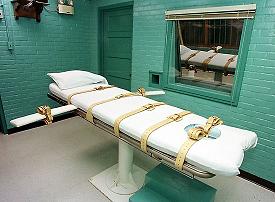

Arkansas’ troubled death penalty process

by May 31, 2016 6:18 pm 283 views

Editor’s note: Justin Allen is a partner with the Little Rock-based law firm of Wright Lindsey Jennings. He leads the firm’s governmental relations group. Opinions, commentary and other essays posted in this space are wholly the view of the author(s). They may not represent the opinion of the owners of Talk Business & Politics.

–––––––––––––––––––

The State of Arkansas hasn’t executed a death row inmate since November of 2005. This de facto moratorium has been caused by numerous lawsuits filed by death row inmates challenging the State’s lethal injection process.

It appeared that executions would resume in Arkansas, and elsewhere, after the United States Supreme Court issued its ruling in the Kentucky case of Base v. Rees. In 2008, by a vote of 7-2, the Court upheld the constitutionality of Kentucky’s three drug protocol, which mirrored the protocol utilized in most other states, including Arkansas. Despite that fact, executions did not resume in Arkansas.

After the ruling in Base, the lawsuits in Arkansas took a new tact. Rather than asserting a claim of cruel and unusual punishment, death row inmates argued that the process utilized by the Arkansas Department of Corrections did not comply with the lethal injection law adopted by the General Assembly. The State addressed those arguments by amending the law in 2009, which then led the inmates to pivot and argue that the new law provided too much discretion to the Department of Corrections. The Arkansas Supreme Court, in 2012, agreed with the inmates on that point and invalidated the State’s lethal injection law.

In 2013, the General Assembly passed a new lethal injection law which, as expected, was challenged by the inmates on similar grounds as the previous law. This time, the Arkansas Supreme Court, in a 2015 opinion, upheld the new law and the process established in it for the Department of Corrections.

By this time, a new problem had developed. States were struggling to obtain the drugs necessary to carry out executions because manufacturers were prohibiting the use of their products in the lethal injection process. Arkansas was no exception as suppliers of the drugs were declining to provide the State with additional product. While the State does possess a sufficient amount of drugs to carry out some executions, those executions are likewise on hold because of litigation. Because of the resistance of manufacturers to supply their product for executions, some states passed laws that would keep the source of the drugs a secret. The hope is that some suppliers will be willing to provide drugs if not subject to the public scrutiny associated with it.

By this time, a new problem had developed. States were struggling to obtain the drugs necessary to carry out executions because manufacturers were prohibiting the use of their products in the lethal injection process. Arkansas was no exception as suppliers of the drugs were declining to provide the State with additional product. While the State does possess a sufficient amount of drugs to carry out some executions, those executions are likewise on hold because of litigation. Because of the resistance of manufacturers to supply their product for executions, some states passed laws that would keep the source of the drugs a secret. The hope is that some suppliers will be willing to provide drugs if not subject to the public scrutiny associated with it.

Arkansas passed such a law in 2015, which the death row inmates quickly challenged. The inmates allege that they are entitled to know the source of the drugs to be used in their execution. They are concerned that the State may use unreliable or dangerous drugs without their knowledge, which could constitute cruel and unusual punishment. That case was argued to the Arkansas Supreme Court on May 19, and a ruling could come as early as this week.

A ruling against the State on this issue will further prolong the moratorium on executions in Arkansas. The drugs in its possession are about to expire and the prospects of obtaining new ones, without the secrecy provision, seem very slim.

A ruling for the State, on the other hand, still doesn’t mean executions will resume. Since 2005, inmates have pursued various types of legal challenges and Arkansas courts, both state and federal, have been willing to stay executions based on those challenges. The chances of that process continuing seem strong even if the secrecy provision is upheld.

Either way, it’s possible that practical and legal obstacles could delay executions in Arkansas for many more years to come. That fact might lead policy makers to examine the future of the death penalty in Arkansas and ask the question: “Is it worth it anymore?”

Having said that, I don’t expect Arkansas will abolish the death penalty anytime soon. But, unless our courts reverse the trend of the last decade, we should be prepared to continue this vicious cycle.