Drones at the forefront of improving soybean yields, profits

by July 12, 2020 9:43 pm 609 views

Soybeans originated in China thousands of years ago, and a few U.S. farms grew the beans prior to the Civil War. The crop was mostly used to feed livestock. During the war, the beans were used as a substitute for coffee and were referred to as “coffee berries.”

At the turn of the 20th century, soybean use exploded as scientists discovered the crop had a high level of protein and meat was scarce during and after World War I. The usefulness of the crop grew, and by the 1950s the U.S. was the top soybean producing country in the world. Ironically, China would become the top soybean importer in the world.

Scientists at the University of Arkansas are trying to develop ways to maximize the crop’s protein potential.

High throughput genetic analysis is a tool that allows researchers to analyze a lot of DNA data in a short period of time. Agri scientist Larry Purcell uses it to evaluate thousands of agricultural test plots at once. He studies these tests plots from the air.

Using an off-the-shelf aerial drone, Purcell can identify those soybean plants that have the genetic makeup, or genotype, for high rates of nitrogen fixation. This biological function is important for producing grain with high protein concentration.

Purcell is a distinguished professor of soybean physiology for the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture.

Soybeans account for about $1.5 billion of Arkansas’ agricultural economy, according to the 2019 Arkansas Agriculture Profile, published by the Division of Agriculture. Growers have planted about 2.95 million acres of soybeans in 2020, according to the United States Department of Agriculture. The acreage is a rebound from 2019’s 2.65 million acres, an 11% increase. The modest uptick had been anticipated by analysts, after farmers made their crop acre declarations earlier in the spring.

The economic value of soybeans, Purcell said, comes from the oil and protein content of the seed. Higher concentrations of either of these, particularly with high yields, increases the value of a farm’s soybean crop.

What Purcell set out to do, with support from the United Soybean Board, was to identify soybean genotypes that are especially efficient in making their own nitrogen supply through nitrogen fixation. From those, he wanted to identify genetic markers that would indicate a plant’s ability to do this. His research was recently published in Nature Scientific Reports.

To reach this goal, Purcell needed help. He enlisted Avjinder Kaler, a former graduate student in the University of Arkansas’ Dale Bumpers College of Agricultural, Food and Life Sciences and later a post-doctoral researcher for the Division of Agriculture. Kaler, now an adjunct professor at UA and a data scientist at Benson Hill, a crop improvement company in St. Louis, focused on the genetics work.

Purcell also had collaborators within the Agricultural Experiment Station, at the USDA Agricultural Research Service and the University of Missouri.

As in other crop plants, nitrogen is a key nutrient for protein production in soybeans, Purcell said. Most other crops require nitrogen fertilizer to acquire what they need. But soybeans are legumes, meaning that they accumulate nitrogen gas from the air and, through a symbiotic relationship with soil microbes, convert, or “fix,” it into a form the plant can use to grow and produce protein. In effect, they produce their own nitrogen fertilizer through nitrogen fixation.

“If a plant can access more nitrogen, that allows it to produce more protein,” Purcell said.

Nitrogen is a major component in chlorophyll and a plant enzyme known as RuBisCO, both key in producing fuel for plant growth and seed development. Nitrogen and chlorophyll both concentrate in plant tissues, and the concentrations in the leaves are indicative of those throughout the plant. Traditional means of measuring those concentrations require taking plant tissue samples for analysis in a lab.

Purcell wanted something faster and non-invasive, and that led him to drones.

In earlier research, turfgrass scientists Doug Karcher and Mike Richardson, professors in the Division of Agriculture’s horticulture department, demonstrated that the green shades of grasses, as measured by digital imaging, can be correlated to their nitrogen and chlorophyll content. They found that hue, saturation and brightness, or HSB — color values inherent in the images that are easily measured by photo editing and other imaging software — could provide consistent, accurate measurements of color values.

In earlier research, turfgrass scientists Doug Karcher and Mike Richardson, professors in the Division of Agriculture’s horticulture department, demonstrated that the green shades of grasses, as measured by digital imaging, can be correlated to their nitrogen and chlorophyll content. They found that hue, saturation and brightness, or HSB — color values inherent in the images that are easily measured by photo editing and other imaging software — could provide consistent, accurate measurements of color values.

Karcher and Richardson used image analysis software that combined each of the HSB values into a single value that could be compared between turfgrass varieties and give an accurate indication of nitrogen and chlorophyll content. They call it the Dark Green Color Index, or DGCI, derived from HSB by a calculation that renders a value between zero and one.

The higher the DGCI value, the better the nitrogen concentration.

Purcell worked with Karcher to apply this imaging tool to assess the nitrogen utilization of corn plants, a research project Purcell is still pursuing with Division of Agriculture soil fertility scientist Trent Roberts.

DGCI was the non-invasive tool Purcell was looking for to measure the nitrogen concentration of soybeans plants.

But he didn’t want to analyze one plant at a time. Purcell wanted to screen many plants quickly. The changing position of the sun in the sky changes the quality and color of daylight throughout the day, and that makes a comparative analysis of multiple plants difficult, if not impossible. Useful digital image analysis means having to narrow the window of opportunity for image capture on any given day.

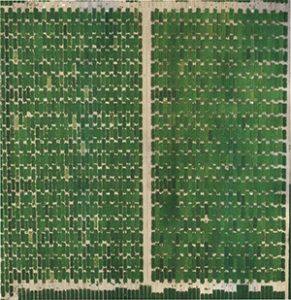

In his research, Purcell screened 200 genetically distinct soybean genotypes from the USDA Soybean Germplasm Collection. These 200 selections represented plants from 10 countries.

“This collection is a source of genetic diversity from which we hoped to find desirable traits breeders can use to develop high-yielding varieties,” Purcell said.

Test plots from each genotype were planted in replicated research trials laid out at three Division of Agriculture research sites across Arkansas: the Milo J. Shult Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Fayetteville, the Pine Tree Research Station near Colt, and the Rohwer Research Station in Desha County. Each location offered a different environment in terms of climate and soil.

That’s a lot of ground to cover. Fortunately, Purcell had a solution. He pioneered the use of unmanned aerial systems, or drones, to screen large numbers of plants.

First, Purcell had to determine that the DGCI index from the soybean canopy of an entire plot was as meaningful as that from a single plant. That proved to be true. With this tool in hand — or rather, in the air — Purcell screened those 200 genomes in replicated plots in three locations and identified those with the highest DGCI.

The next step was to identify genetic markers associated with high DGCI, Purcell said. Kaler obtained more than 42,500 single nucleotide polymorphisms, known as SNPs (commonly pronounced “snips”), for all 200 genomes from Soybase, an online database of genetic information funded by USDA-ARS.

A SNP is a single variation in the genetic code of an organism. A single SNP has a small effect on an organism’s appearance or function, but multiple SNPs can add up to significant differences in traits, like whether a plant does a better job of concentrating protein in its seeds.

They are also useful as genetic markers. Their presence in a crossbred plant can inform a breeder whether it inherited desired traits from its parents.

Using a host of advanced genetic tools with complex names like “genotyping and linkage disequilibrium” and “genome-wide association analysis,” Kaler and Purcell identified 45 SNPs significantly associated with high DGCI values across all three environments.

Out of those 45 SNPs, they identified 30 alleles, a technical term for variations of a particular gene, that are linked with an increase in DGCI value.

“It’s gratifying to see that we can use something as simple as an aerial photograph that reflects complex biochemical processes important for nitrogen fixation,” Purcell said.

The DGCI data Purcell accumulated helps breeders know which soybean genomes make good candidates for crossbreeding. And the genetic markers help them track which offspring from those crosses have the desired nitrogen fixation trait.

The information, Purcell said, gives breeders useful tools they can employ to develop improved soybean varieties that add value and profit to Arkansas farmers’ crops.