Hawkins says she’ll stay involved with ASU Heritage Sites upon retirement

by April 9, 2019 7:41 pm 705 views

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

During the smoldering hot summer of 1999, Dr. Ruth Hawkins, director of the Arkansas State University Heritage Sites, had a goal in mind. She wanted to establish a National Scenic Byway in the Arkansas Delta Region and she had been working with several elected officials to make that a reality.

To establish the Crowley’s Ridge byway, there needed to be attractions or places for tourists to visit. Northeast Arkansas has a number of rich historical features, which ASU, under the leadership of Hawkins, built into heritage sites. Those sites include the Southern Tenant Farmers Museum in Tyronza, Lakeport Plantation in Lake Village, the Hemingway-Pfeiffer Museum and Educational Center in Piggott, and the Historic Dyess Colony: Johnny Cash Boyhood Home in Dyess.

Nearly 20 years later, Hawkins plans to retire now that the university’s heritage site system has been built, she told Talk Business & Politics. About 75,000 people visit the sites each year, she added.

“We never intended for ASU to own property … The sites have two purposes. One, is to serve as an educational resource for students of all ages, and secondly to act as economic catalysts for the communities they serve,” Hawkins said.

The first heritage site built was the Hemingway-Pfeiffer Museum, and Educational Center in Piggott. Ernest Hemingway, the Nobel Prize and Pulitzer Prize winning author, wrote part of “A Farewell to Arms,” an iconic 20th-century novel, during his many trips to Clay County during the 1930s. He was married to a woman named Pauline Pfeiffer who was from Piggott.

Hemingway, who wrote other classics such as “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” “The Old Man and the Sea,” and “The Sun Also Rises,” ultimately came to Arkansas because of a flood. High waters along waterways in Northeast Arkansas stranded Pauline’s father, Paul Pfeiffer, in Clay County.

At the time, his family lived in St. Louis, but he was looking for farm land in which to invest. He decided to relocate, and in 1913 Pauline moved with her family to Piggott. Her father bought thousands of farm acres in the region.

She was working as a journalist for Vogue in Paris when she met Hemingway. She was friends with Hemingway and his first wife, Hadley, but it wasn’t long before an affair simmered between Hemingway and Pfeiffer, according to historical accounts. He divorced Hadley and married Pauline in 1927.

ASU acquired the makeshift barn that Hemingway used as a writing studio in 1997. It was restored to its original condition and the first heritage site museum was born, Hawkins said.

Each of the sites has been an ambitious project, none more so than the restoration of the Johnny Cash boyhood home in Dyess, she said.

Hall of Fame Musician Johnny Cash grew up in Dyess during the Great Depression. Ray and Carrie Cash brought their family to the Dyess Colony in 1935, according to historians. The Cashes moved to Dyess with their five children, Roy, 13; Louise, 11; Jack, 5; J.R. (Johnny), 3; and Reba, 1. Joanne and Tommy were born in Dyess.

During that era, the area was more swamp than usable farm ground. Workers drained the swamp and 500 farm families, including the Cash family, received 40 acres and a mule through a federal government aid program. Rice and cotton were grown. Johnny Cash, along with his brother, Jack, worked the family farm and attended school. Work in the fields was grueling. At night, Johnny and Jack spent a lot of time in their room.

Their father, Ray was a strict disciplinarian who worked extremely hard. The children toiled in the cotton fields alongside their parents. Johnny and his siblings were raised in humble circumstances and the Cash children were taught to work for what they earned.

Jack died in a wood cutting accident as a youth. Music historians attribute Cash’s dark, brooding style to his brother’s unexpected death. Johnny served in the military after high school. He came home periodically to visit his parents before moving to Memphis in 1956. Cash returned to his old homestead years after he became internationally famous with songs such as “Folsom Prison Blues,” “Walk the Line,” “Ring of Fire,” and others. His battles with drugs and alcohol were well-documented, and he is often referred to as “The man in black,” a reference to the all-black clothing attire he wore during performances.

ASU began restoration on the Cash childhood home in 2011. The dwelling was restored to its original condition and an administrative building built into the old Colony theatre. The project cost about $3.5 million. The heritage festival began after a series of successful concerts were held at the ASU Convocation Center starting in 2011 honoring Johnny Cash’s legacy. A festival is held at the childhood home each fall, too.

Daughter Joanne Cash often visits the house, and it’s not uncommon for her to greet visitors that come to the site, Hawkins said.

“The Cash family has been very invested in the project,” Hawkins said.

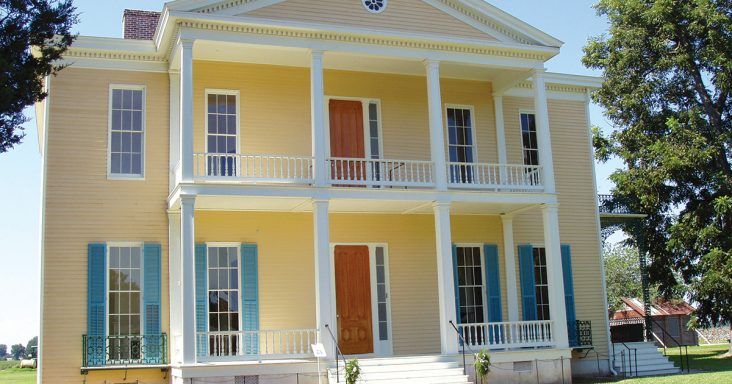

ASU began work on the Lakeport Plantation in 2001. The plantation, originally built in 1859, is the last plantation still standing along the Mississippi River. The Lakeport Plantation researches and interprets the people and cultures that shaped plantation life in the Mississippi River Delta, focusing on the Antebellum, Civil War, and Reconstruction periods.

The Lakeport Plantation house was placed on the National Historic Register in 1974 and was designated in 2002 as an official project of the Save America’s Treasures program through the National Park Service and the National Trust for Historic Preservation, according to ASU.

The plantation has remained in continuous cotton production since the 1830s when slaves carved it from the heavily-forested Arkansas frontier. It documents the agricultural development in the region and the accompanying changes in the African-American experience. These changes include the transition from frontier and plantation slavery, to sharecropper and tenant farmer systems, to agricultural mechanization and the resultant mass exodus of African-Americans to factories in the North, to large-scale corporate farming.

Hawkins said she will miss working on the heritage sites when she retires later this year, but she’s proud of what she, her team and the university have been able to accomplish during the last two decades. There probably won’t be enough money available to buy any new sites in the near future, so the development of the educational tools and programs at the sites that already exist will be the primary focus.

She might not be in charge of the program, for much longer, but she will volunteer. “I’ll still be around,” she said.