Tight domestic trucking capacity increasing cost for consumers

by May 7, 2018 2:25 pm 937 views

As prices rise and investors keep tabs on inflation that might slow industry growth, tight capacity for truckload and some rail carriers has led them to invest in their fleets to expand capacity.

As things stand now, there is increasingly more stuff to be shipped and less stuff in which to ship it.

An exception is that capacity such as ocean freight isn’t as constrained, said John Kent, director of the Supply Chain Management Research Center in the Sam M. Walton College of Business at the University of Arkansas. Yet, tight domestic capacity is leading costs to rise, specifically in the truckload segment of the transportation sector, which carries about 71% of the nation’s freight tonnage, according to the trade group American Trucking Associations.

Demand for truckload and specialty carriers, such as temperature-controlled and food carriers, has impacted capacity, leading spot prices in the truckload segment to rise, Kent said. In March, dry-van spot rates rose 32%, from the same month in 2017, according to DAT Solutions. Industries that use the most capacity include agriculture as bulk commodities such as grain are transported by rail, truck and barge. The construction and retail sectors also comprise of a significant portion of capacity along with overnight shippers that require air capacity.

As transportation prices increase, consumers are expected to bear most of the costs, Kent said. Capacity started to tighten about two years ago, before Donald Trump was elected president and the stock market rallied as a result of optimism following the election. When capacity starts to loosen could depend on inflation, as Kent expects it will impact economic growth, possibly in less than two years.

Over the past 10 years, trucking companies have been through tough times, and growth was constrained, Kent said. They kept equipment longer and purchased less of it. However, as demand has risen, carriers have started to purchase trucks again and are working to catch up with demand.

In March, medium and heavy duty orders of trucks exceeded 70,000 in North America, for only the fourth time, said Kenny Vieth, president and senior analyst for ACT Research. Orders of class 8 trucks, or the biggest class of big rig, more than doubled to 46,900 units, from the same month in 2017. It was the third consecutive month orders were greater than 40,000 units.

In late March, transportation stocks experienced a decline as a result of cost pressures related to inflation and the large number of class 8 truck orders, according to senior research analyst Benjamin Hartford and research analyst Andrew Reed, both with Robert W. Baird & Co.

Investors were skeptical on whether contract truckload pricing will rise as expected and have doubts over whether the price increases will be retained by carriers and not absorbed by cost inflation. Hartford and Reed expect contract prices to rise between 5% and 10% in the 2018 bid season.

Kent said the truckload industry has a lot of competition and is easier to enter than the parcel, express delivery or air freight sectors. When demand rises in the truckload industry, price rises accordingly. But in the other sectors such as express delivery, price doesn’t fluctuate similarly.

“UPS, FedEx and the post office are the three oligopolistic competitors there,” Kent said. “And so the barrier to entry in that e-commerce space for those packages, for a multibillion-dollar sorting facility like FedEx or UPS has — it’s hard for someone to go create one of those.”

For every product a consumer purchases, it has a percentage of the cost that can be attributed to truckload transportation, Kent said. That percentage of the cost is expected to rise by the amount the rates increase. For a gallon of milk, for example, about 30% of the cost is transportation. Based on that ratio, increased transportation costs have led the price of milk to rise about 9% from a year ago. Transportation costs account for nearly 50% of heavy, inexpensive construction materials, such as a 60-pound bag of concrete mix or a two-by-four.

On the other end of the spectrum, transportation costs account for a much smaller percentage of the overall cost of goods for expensive, lightweight items such as pharmaceuticals.

MANAGING COSTS

One of the factors impacting cost and capacity has been where shippers build fulfillment centers to help manage transportation costs, Kent said. Multiple centers throughout the United States would allow shipments to reach their destinations via truck transportation, and without having to resort to more expensive shipment options such as air freight. If one can keep a shipment’s freight destination to less than 500 miles, a truck can haul it on the same day.

Eliminating the transportation cost might also be an option for fresh food suppliers. A store could set up a greenhouse in the parking lot to cut out the cost.

“Your customers would have fresher food,” Kent said. “And the transportation cost would be zero or near zero.”

Kent said innovation in the supply chain can help reduce costs, which might include using robots and drones to deliver items. Also, technology is expected to impact capacity as it relates to the driver shortage. Platooning is an automated driving technology that allows trucks to communicate with each other, allowing them to follow at much closer distances and improving fuel efficiency. Self-driving trucks should help the driver shortage, but the technology likely won’t be used for nearly 10 years.

Over the years, capacity usage has changed with computers and allowed the better use of equipment. Dimensional pricing also will impact capacity, as it will keep shippers from shipping air. If a truck is filled to capacity better, fewer trucks will be needed to complete shipments. That will be evident with visibility systems and can be tracked with big data, allowing the transportation sector to make smarter decisions with existing capacity.

“We could use our rivers more, the Arkansas River,” said Kent, adding that waterborne shipping is the least expensive mode of freight transportation. “We could bring containers up to Fort Smith and reduce the need for shipping them from New Orleans to Fort Smith, or from Kansas City to Fort Smith, or from Memphis to Fort Smith on a truck.”

RETAIL, ECONOMIC IMPACT

Retailers are concerned about the capacity crunch driving shipping rates higher, said Dr. Brian Gibson, executive director for the Center for Supply Chain Innovation at Auburn University. In a recent survey of 100 large retailers, he found a majority mentioned capacity constraints resulting in rising shipping rates for truckload. They also had concerns around final mile delivery and lack of capacity in this space amid rising consumer demand.

“Retailers don’t seem to be as concerned with getting freight from distribution centers to stores because, in many cases, they are using private fleets and secure dedicated contract services,” Gibson said. “But getting freight from the manufacturers into the company, and then getting items out to the customers remains quite challenging. We are seeing more retailers use less-than-truckload (LTL) carriers for delivering bulky items, like bed frames or kayaks, directly to consumer homes. This is an opportunity for the LTL segment, for sure, as more items are ordered online in the future.”

Gibson said with nearly 100% of the available trucks already in use, it’s getting harder for retailers who rely on outside carriers, either through dedicated contracts or spot market. Gibson said more retailers are trying to switch to dedicated contract services from spot market to ensure they can get freight hauled. It generally costs more for that guarantee.

But recently, with increased overall demand coming from many sectors outside retail, the spot market capacity is also stretched very tight.

“This is the first time I have ever seen spot market prices higher than contract rates. But there is an inversion in the rates, and those using spot markets are paying as much as 35% more than a year ago,” Gibson said. “Contract prices are up 8% year over year.”

INFLATION PRESSURES

Colby Beland, vice president of sales and marketing for Fayetteville logistics firm CaseStack, said retailers and suppliers are feeling the capacity crunch, and it’s showing in recent quarterly earnings. General Mills CEO Jeff Harmening recently cited higher transportation costs for the company’s third-quarter profit miss.

“The cost pressure we’re seeing is even higher than we first thought,” Harmening noted in the March 21 earnings call. “We’re now having to go out to the spot market for close to 20% of our shipments versus the historic average of about 5%, and those spot market prices can be 30% to 60% higher than our contracted rates.

“Higher freight costs are impacting our raw material prices … [and] the cost to ship materials from our suppliers to our factories has risen significantly. And we’ve seen higher prices in some key commodities further heightening the inflationary dynamic.”

Tyson Foods President and CEO Tom Hayes has said the food giant is looking at $200 million ore more in added costs this year because of tightening freight capacity and rising costs.

“These higher costs are included in our overall outlook. We’re assuming we’ll recover the majority of these costs through higher pricing,” Hayes said, as passing the cost through is something they have to do and ultimately, the consumer is going to pay for it.

Beland said the earliest capacity ease would likely be mid-2019, unless there is some national shock to the economy that would push the U.S. into recession. With rates expected to rise through the summer and into the peak shipping season for the next holiday, Beland doesn’t see any way retailers or suppliers will be able to bear all the added costs.

“It will trickle down to the consumer in the form of higher retail prices,” he said. “I don’t know when or how much, but inflationary pricing is a real possibility.”

Trucking analyst Donald Broughton recently noted shipments rose 11.4% and 11.9% from a year ago in February and March, respectively. He said rising shipments continue to exacerbate the tight capacity in the trucking sector. Pricing power has erupted and is sparking overall inflationary concerns in the broader economy, he noted.

Broughton said there is some concern for long-term inflationary pressure from this capacity shortage. Beland cited mid-2019 before there is added equipment, but it could be longer if companies can’t find drivers to put in the seats. Beland said carriers will have to raise driver pay, also an inflationary act.

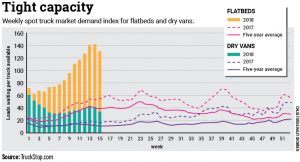

Truckstop.com reports about 140 loads sitting on a given dock waiting for every one flatbed truck. The five-year average is 40 loads. Beland said the flatbed market is the tightest in part because it serves the construction industry, which is building again, and the oil and gas industry, which is drilling and fracking again. Also, the electronic logging device (ELD) mandate requiring new equipment to monitor driving hours has drained between 5% and 15% of the capacity out of the market. Beland said geopolitical concerns in the Middle East and the NAFTA renegotiation are causing steel and aluminum to be purchased in bulk from manufacturers as a hedge.

Beland said the dry van segment is roughly 50% spot and 50% contract. In the spot market, roughly 40 loads were waiting on the dock for every available truck last month. The demand is up from the five-year average of 10 loads waiting per truck, according to Truckstop.com.

“It’s a carrier’s market because they can pick and choose which shippers they want to do business with. They can charge whatever rate they want, and typically there is no assurance of expected service levels, which is why you are hearing/seeing as many shippers trying to convert to contracted rates versus the spot environment,” Beland said. “But if carriers don’t have capacity available, then they are likely to keep the shipper in the spot market, so they can make hay while the sun shines.”

Beland said demand is outpacing supply, which leads to inflationary pricing. When the load-to-truck ratio is upside down, rates increase. He said as long as capacity stays tight, shippers will pay more to ship goods.

“Shippers who adhere to spot quotes are betting against a strong freight market and believe all factors indicate rates will decline for the foreseeable future,” Beland said. “For now they are paying more. Shippers who lock in to contract rates are hedging their bets against escalating rates and limited capacity. But as drivers remain in demand, carriers will have to raise driver pay, and those costs will trickle down into higher contract rates costing shippers more in the future.”

Talk Business & Politics Senor Report Kim Souza contributed to this report.