Phillips County memorial to note one of worst race riots in the U.S.

by April 9, 2018 7:32 pm 4,821 views

King cotton’s prices were on the rise, but the black sharecroppers who picked it were not benefiting. It was Sept. 30, 1919, and the harvest was about to get underway.

About 100 sharecroppers met at a church in the town of Elaine, a small town in Phillips County that sits in the vast Mississippi Delta Region. Armed black guards protected the people inside. Suddenly, white men appeared outside.

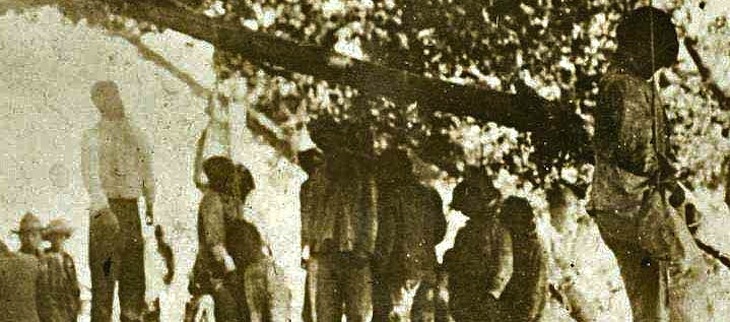

No one knows definitively who fired the first shot, but during an altercation bullets flew, and one white man was killed. Blacks outnumbered whites in that part of the county by at least 9-1 and a panic ensued. Whites poured into that part of the county and formed an armed mob. The 1,000-man mob began to slaughter blacks.

Historians don’t know how many blacks were killed, and estimates have ranged from 20 to 800. But one thing is sure, Arkansas Department of Heritage Director Stacy Hurst told Talk Business & Politics: the Elaine Massacre was one of the worst killing sprees in U.S. history between whites and blacks, and it needs to be remembered.

“It is a very important historic event in Arkansas. … It’s time to acknowledge it. It’s time to talk about it,” she said.

A groundbreaking for a memorial will be held Tuesday (April 10) in Helena. The memorial will be placed in the vicinity of the county courthouse and the federal courthouse building, Elaine Massacre Memorial co-chair David Solomon told Talk Business & Politics. A nonprofit organization was formed about three years ago to build a memorial, he said. How much it will cost was not disclosed.

The memorial will be in the shape of an arch, and will not have any victims’ names. There are only 10 people whose names are known, and Solomon said he thinks at least 200 people died. It will be similar to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, he said. The memorial is slated to be dedicated Sept. 29, one day before the hundred year anniversary of the massacre.

Helena was chosen for the memorial for several reasons. Trials for the blacks tried for crimes were held in the city, and a lot more people will visit it, he said. Elaine is a relatively desolate town, and it would be hard to direct tourists to the town, he said.

Details of how the massacre unfolded are scant at best, Arkansas History Commission Chairman Jason Hendren told Talk Business & Politics. The story was poorly recorded at the time, and as time passed, a lot of the facts have been lost as people involved died and moved away.

“The actual facts remain murky,” he said.

The summer leading up to the clash between blacks and whites in Phillips County was intense around the country. Racial tensions were high across the country. Race riots broke out in cities and towns nationwide. There were riots between blacks and whites in Chicago and Washington D.C., but the biggest was perhaps in Elaine.

After the firefight at the church, the white armed mob invaded Elaine. Whites from as far away as Mississippi and Tennessee joined. Unarmed black men, women and children were shot down in the streets. Rumors spread that the black community planned a “take over” and it further fueled white fears. A PBS documentary about the event described the fight in Elaine as a literal war between the races. Some blacks armed themselves and tried to fight back, according to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Those who fought back were targeted.

As the slaughter unfolded, government officials scrambled to act. Hundreds of soldiers were sent from Camp Pike (near Little Rock) to stop the mob. Soldiers disbursed the mob, and rounded up hundreds of blacks, according to BlackPast.org. There were reports of torture. Many were only released after their white employers asked for them to be released.

Before the episode ended, 122 blacks were charged with crimes, and 12 were charged and convicted of capital murder. The murder convictions were eventually overturned after the men spent years in prison. Not a single white was charged with a crime.

Many would not talk about the four-day killing spree, Hendren said. There are reports that bodies were dumped into the Mississippi River, and some were left in fields to rot, but it’s hard to verify because no one spoke out at the time. Neither community, white or black, wanted to revisit it for several years, and it was largely forgotten, he said. No one knows the number killed, but its significantly more than the confirmed deaths, he said.

Hendren, Hurst and Solomon agree this is probably the most violent interaction between the races in Arkansas’ history, and is one of the most violent ever in the country. A small ceremony will be held at the ground breaking and several speakers will talk, Hendren said.

“It’s going to be a solemn occasion,” Hendren said.