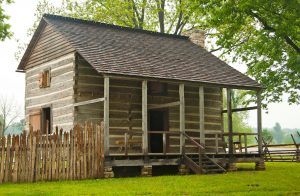

Two oldest structures on their original foundations west of the Mississippi River located in northern Arkansas

by December 6, 2017 5:58 pm 5,383 views

Historic preservationist Joan Gould loves to search the off-beaten paths and back roads in Arkansas. She was on one of these adventures in northern Randolph County near the town of Dalton when she fixated on a house. It had additions built onto the original structure, and it outwardly looked like an older, but typical house in this part of the state.

It was not.

She talked the house tenants into allowing her to peel back the drywall and it exposed something unexpected and marvelous. Logs, that date the original construction to 1828 were revealed. It’s been more than 14 years since Gould made her find, and now the restored Rice-Upshaw House is operated by the Researching Early Arkansas Cultural Heritage (REACH), a non-profit organization operated through the Black River Technical College Foundation, REACH Project Coordinator Jessica Bailey told Talk Business & Politics. It cost more than $2 million to restore the house and the nearby William Looney Tavern. The two structures are the oldest still on their original foundation west of the Mississippi River, she said.

“It’s a unique part of our history,” Bailey said.

The structures place in history began in 1802 when 17-year-old William Looney left his east Tennessee home with two African American slaves. He journeyed to the Eleven Point River Valley in present-day Randolph County, according to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Looney decided to settle in the area. It had rich fertile soil, and there are five navigable rivers in the region.

A few years later, Looney’s neighbor in Tennessee, Reuben Rice arrived in the Dalton area. Rice became successful in the goods trade, and by 1828 he built the house. It was originally a mercantile, where craftsmen sold and exchanged goods, Bailey said. During this time Looney worked as a financier, and family traditions claim he made about 1,500 gallons of brandy per year. He was a militia captain among his many endeavors.

River traffic continued to grow, and by 1833 Looney decided to build his tavern along the river. Taverns of this kind served as way stations to river travelers in those days, according to historians. It would be many years before either the house or the tavern would be transformed into homes. Looney died in 1846, and it was reported he owned 13 slaves in addition to several businesses and interests. Rice died in 1850, but there are no records indicating his possessions or wealth.

After Gould made her find, the East Arkansas Settlement Study confirmed the house and tavern were built almost 200 years ago. In 2004, BRTC officials began formal talks about restoring the structures. Jean Upshaw and family, and Jack and Christina French, descendants of Rice and Looney, donated the structures to the college in 2006. The Arkansas Natural Cultural Resources Council provided the grant money to restore the structures. Work was completed in 2011.

During the restoration, the house had to be lifted off the ground, and the tavern had to be dismantled, Bailey said. Many artifacts dating to the era including bones, pottery shards and others were found. The Arkansas Archaeological Survey has spent years identifying and cataloging the artifacts, Bailey said. The founding families have donated money to buy cabinets to display the artifacts and the hope is this part of the project will be completed in the near future, she said.

The Rice-Upshaw House and the William Looney Tavern may be two of the most historic buildings in Arkansas, but it can be difficult for history tourists to find them. Dalton sits in a remote part of Randolph County, several miles from any major highways. The house is easily accessed once a tourist reaches the area, but the tavern is harder to get to. The house and tavern are only about a mile a part, but it’s about 11 miles on the road to travel between the two.

Each year about 1,000 people visit the historic sites, and in the coming years there will be an effort to increase those numbers. It’s remote location posses a problem, and the lack of staff at the facilities. It’s only open from April to October during limited hours on every Tuesday and the second Saturday of each month. School groups visit the sites, and area schools do projects about their historical importance.

“We plan to expand our workers and staff. … It’s an important piece of history,” she said.