What we’ve done in the name of national security

by April 3, 2017 12:26 pm 586 views

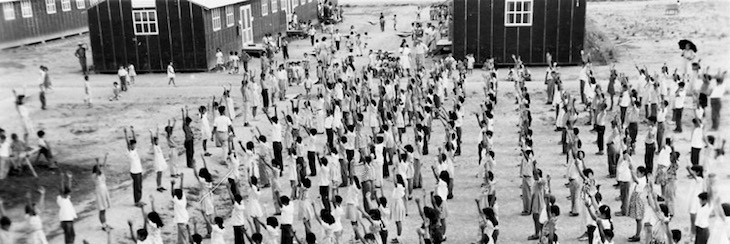

Detainees at the Japanese internment camp in Rowher, Ark.

The first few months of Donald Trump’s presidency has seen a flurry of activity. Much of this has been enacted through the president’s power of executive orders. Of course, as many know, the most controversial of these is the travel ban order. The newest addition to this includes laptops on certain flights to and from the Middle East. Trump claims all this is being done in the interest of national security to protect Americans from the threat of terrorism. This got me to thinking about another time a president enacted a similar order in the so called interest of national security.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 came on the heels of the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Signed on Feb. 19, 1942, the new order gave the secretary of war the ability to designate military areas where all residents could be evacuated. This set the stage for the removal of nearly 120,000 people of Japanese descent from “sensitive” areas of the west coast. Once the executive order was in place, President Roosevelt quickly created the War Relocation Authority (WRA) for the “relocation, maintenance, and supervision” of the Japanese American population. What this really meant is that people of Japanese descent, nearly 70,000 (out of the 120,000) which were American citizens, would be detained for the duration of the war in relocation centers.

The bombing at Pearl Harbor fueled wartime hysteria and brought race tensions against the Japanese back to the forefront. The main concern, and “justification” for the WRA relocation, was to prevent Japanese people from causing another surprise attack on the west coast. Many white Americans thought they were spies for the Japanese emperor and that relocation was the only way to prevent another atrocity. As far as the WRA was concerned they wanted to keep people “a safe distance from strategic works.” For the War Department it was a national security issue, but at its core it was a blatant violation of the constitution.

Ten sites, mostly in the west, were chosen to house the many people uprooted from their homes and lives (often with very short notice). Two camps were established in California as well as Arizona. In addition, there was one camp each in Colorado, Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming. The last two camps were the furthest east, and by all accounts the most remote. These were in two small, rural towns in southeast Arkansas, Jerome and Rohwer. Prior to the internment camps, the population of both towns combined did not exceed 500. That changed as the camps were built, and the population soared to 16,000.

Rohwer was the larger of the two Arkansas camps with a peak population of 8,475. The camp was in operation from Sept. 18, 142 until Nov. 30, 1945. Jerome’s highest number of residents was 7,932, and it had the shortest span of any of the 10 camps. It was only operational from Oct. 6, 1942 to June 30, 1944. Nearly 65% of the residents of Rohwer were considered Nisei, or second generation American born citizens. This number was even higher at Jerome with some 66% Nisei. If you look at the statistics from any of the ten camps, they are all relatively similar in demographics, so it begs the question why the US government was so quick to incarcerate thousands of its own. The answer, in Arkansas at least, can be traced to the Jim Crow system of segregation and disfranchisement.

Arkansas’ governor during World War II, Homer Adkins, was much like most southern governors of the time in that he drew a hard color line. This extended to the Japanese internees who made their way to the state starting in 1942. Adkins was opposed to the idea of having internment camps in Arkansas. That is until the federal government stepped in with a lot of money for the state in return for building the camps.

Once he reluctantly agreed, Adkins placed further restrictions on the internees to ensure they would not permanently come to reside in the state after the war. In February 1943 the Arkansas legislature passed the Alien Land Act which prevented any Japanese person, citizen or alien, from purchasing or owning land in the state. Adkins was in favor of the act, and signed it into law though it was later deemed unconstitutional. The crowning blow for Adkins was that he did not want to allow the kids at the camps to attend to school in Arkansas. Nearly 30 percent of the residents of both camps were of school age, but Adkins rationale was that if you allowed the Japanese kids into the schools, then you would also have to allow African-American kids as well.

Despite the racism and blatant unconstitutionality of internment, the majority were American citizens that did everything they could to prove their patriotism, even while residing at the camps. When the federal government created the 442nd combat unit, an all Japanese-American unit, numerous young men of military age from all ten camps volunteered to fight for their country. The soldiers proved their worth in combat as the 442nd became the most decorated unit of its size in the entire war. Japanese American citizens were willing to fight and die for a country that was not always willing to do so for them.

Eventually the federal government apologized to and compensated people of Japanese ancestry in the United States that were torn by internment. While it was 40 years after the fact, the government admitted its mistake. Maybe this is the lesson for the new administration to take into consideration.

––––––––––––––––––––

Editor’s note: Scott Cashion is a history professor at the University of Arkansas at Fort Smith. Opinions, commentary and other essays posted in this space are wholly the view of the author(s). They may not represent the opinion of the owners of Talk Business & Politics.