Arkansas’ balanced budget still producing debt: $16.75 billion owed total

by October 20, 2016 10:10 am 1,486 views

“The old saying is, ‘Amateurs study tactics. Professionals study logistics,’” said Rep. Doug House, R-North Little Rock, a retired National Guard colonel. “I think in politics, amateurs study policy and professionals study budgets.”

House, an attorney and a member of the Joint Budget Committee, has spent a lot of time studying the state budget. And what he has found is Arkansas’ government and other state-related public entities such as schools owe a lot of money – about $16.75 billion counting bonded debt, debt owed by higher education institutions and public schools, employee benefits, and unfunded liabilities in pension plans.

The $16.75 billion equals $5,600 for every Arkansan – a far cry from the $61,000 that is each American’s share of the national debt. Still, the news might come as a surprise to Arkansans who assume the state’s Revenue Stabilization Act ensures it has a balanced budget.

“Congress has a balanced budget,” House said. “They spend whatever they want to, and then they go borrow the money to cover their checks … and we’re doing essentially the same thing.”

House began looking into the state’s debt situation about a year and a half ago at the encouragement of Sen. Jeremy Hutchinson, R-Benton. He said it hasn’t been easy to discover exactly how much the state owes. The Department of Finance and Administration has an online comprehensive annual financial reporting system that is a good source, but the information is not complete.

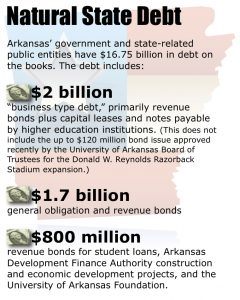

The $16.75 billion figure includes the following.

• $2 billion in “business type debt,” primarily revenue bonds plus capital leases and notes payable by higher education institutions. This does not include the up to $120 million bond issue approved recently by the University of Arkansas Board of Trustees for the Donald W. Reynolds Razorback Stadium expansion.

• $1.7 billion in general obligation and revenue bonds.

• $800 million in revenue bonds for student loans, Arkansas Development Finance Authority construction and economic development projects, and the University of Arkansas Foundation.

Total interest costs for these types of debt for fiscal year 2017 are projected to be more than $170 million. Most of those bonds are 20-year, 2%-4% interest bonds, almost all of them with a 10-year non-redemption provision.

The same is true for the state’s public schools, which, as of June 30, 2015, had $4.1 billion in bonded and non-bonded debt, according to the Arkansas Department of Education. Many of the state’s 237 public school districts have undertaken bonded indebtedness in order to build or improve facilities or make investments in technology. Those districts are responsible for their own debts. However, a state law says if a public school does not pay its bonded debt, the state will sequester state funds and pay the debt for the district. Those students still would have to be educated.

EMPLOYEE BENEFITS, PENSION FUNDS

The state also owes $2.2 billion in other employee benefits, mostly liability for health insurance and also for post-employment benefits, such as unused vacation time, House said.

The news is not all bad. These debts have produced valuable capital assets, such as highways and water systems, as well as educated students. Also, the state has managed the debt well, House said. Interest rates are low. The Arkansas Development Finance Authority handles debt issuances for the state and has been “very shrewd,” he said.

“Rates are very competitive,” he said. “Our bankers, without exception, look to me to have been very fair with us. They give us the very best rates in the prevailing market. Their settlement charges across the board are reasonable as compared with other institutions.”

Finally, the state’s pension plans have $5.95 billion in unfunded liabilities as of the last available audited financial statements on June 30, 2015. On that date:

• The Arkansas Teacher Retirement System’s liabilities were $18,292,611,155, while its assets were $15,035,701,312, a difference of $3,256,909,832;

• The Arkansas Public Employees Retirement System’s liabilities were $9,391,975,712, while its assets were $7,550,242,341, a difference of $1,841,733,371;

• The Arkansas State Highway Employees Retirement System’s liabilities were$1,629,276,087, while its assets were $1,443,476,293, a difference of $185,799,794;

• The Arkansas Judicial Retirement System’s liabilities were $254,713,985, while its assets were $223,123,751, a difference of $31,590,234;

• The Arkansas State Police Retirement System’s liabilities were $403,202,550, while its assets were $279,657,570, a difference of $123,544,980; and

• The Local Police and Fire Retirement System’s liabilities were $2,034,767,448, while its assets were $1,526,181,658, a difference of $508,585,790.

George Hopkins, director of the Arkansas Teacher Retirement System, said his best estimate would be that the ATRS trust fund is worth about $15.05 billon, while the system has about $3.2 billion in liabilities requiring 28-29 years to pay out. The system serves 45,000 retirees with an average benefit of about $23,000 per year, and those retirees consist of a majority female population that lives longer than the general population. It has paid out $250 million more this fiscal year than it has received in contributions. He said the system is in the top 3% of its peer pension plan groups.

House says the pension plans situation is worse than it appears. The plans assume a 7.75%-8% gain every year – a difficult standard to achieve, especially when the next recession inevitably rolls around.

Hopkins said his system assumes an 8% gain and has achieved a rate of 8.2% since its inception. In an era of low inflation, the system is working to set a rate closer to 7.5% and is prepared to lower it further. He said before 2009, benefits typically were increased as a teacher recruitment and retention tool whenever the amortization fell below 30 years. Since 2009, that focus has changed. Numerous acts have been passed that give the ATRS more flexibility in reducing benefits in response to an economic downturn, and the ATRS has instituted numerous rule changes. Before 2009, 60% of each year’s contributions were required to offset the costs of unretired members. That percentage was 49% at the end of the 2015 fiscal year.

FEEDING THE SYSTEM

All of the plans, including ATRS’, rely on payments by public employees. House said that makes it hard to cut government.

“They tore a sheet out of that ‘what the heck’s really going on book’ and let me read it here a while back,” he said. “I was ready on the Personnel Subcommittee to start cutting employees. And the staff pulled me off to the side, and they said, ‘Mr. Representative, you can do what you want to. That’s what your job is, but understand something: If you do not have more employees coming in, that’s how we fund the public employee retirement system. You stop that inflow of new employees and payments they make, you bankrupt that system. Do you understand?’ ‘Yes, I do. Thank you.’”

Hopkins said the Arkansas Teacher Retirement System faces a similar challenge: School districts are outsourcing to private providers functions such as cafeteria services and substitute teachers. He said the system will seek to address that issue during the 2017 General Assembly.

Hopkins said ATRS is evaluating trends on a monthly basis. House has high praise for those administering the plans.

“You can’t ask for better people, more conscientious people about what they’re doing, but the defined benefit system requires lots of administration, requires lots of money to be pumped in because you have guaranteed that you’re going to pay out on the other end,” he said.

10-YEAR DEBT RETIREMENT PUSH

On June 23, House wrote a letter to Gov. Asa Hutchinson; Senate President Pro Tempore Jonathan Dismang, R-Searcy; and Speaker Jeremy Gillam, R-Judsonia, about the state’s debt.

On July 14, Hutchinson wrote House that his administration is considering a debt retirement and tax relief fund that would be funded with surpluses usually going into lower priority activities. Deposited surplus funds could be used to reduce debt. He wrote that the state’s debt had increased over the last nine years by $750 million, mostly for highway bonds, but 83% of the state’s total debt and nearly 91% of its general obligation debt would be paid in 10 years – which doesn’t include new debt the state incurs during that time. He wrote that the Department of Finance and Administration’s Division of Building Authority is developing a facilities master plan, suggesting that the state build or buy more of its own facilities rather than lease them while interest rates are low.

“This is one example of a category of borrowing that we may want to continue since the impact on the budget is a net positive,” Hutchinson wrote.

House wrote the governor that the state within 10 years should retire all existing general obligation bonded debt, establish strict debt management policies, and establish defined contribution pension plans – rather than defined benefit plans – for new state and public school employees. Most private companies and most federal employees have defined contribution plans, where benefits are paid into an account that’s invested rather than having a guaranteed benefit.

Hutchinson wrote that the idea of moving toward defined-contribution plans would result in lower, unfunded pension liabilities. He said the idea would be appropriate for an interim study.

House told Talk Business & Politics that, with prudent management, the state could go from being a debtor to being a creditor within about five years. Instead of borrowing the money to loan to local utilities, for example, it would lend its own money and then keep the interest, increasing the general fund.

“I would love to 100% fully fund our retirement systems,” he said. “I would love to be able to loan money to cities and towns that want to build systems. And I would love for our banks to be in the wealth management business instead of the debt management business for Arkansas. … We could be the lender instead of going to a lender to facilitate that loan.”