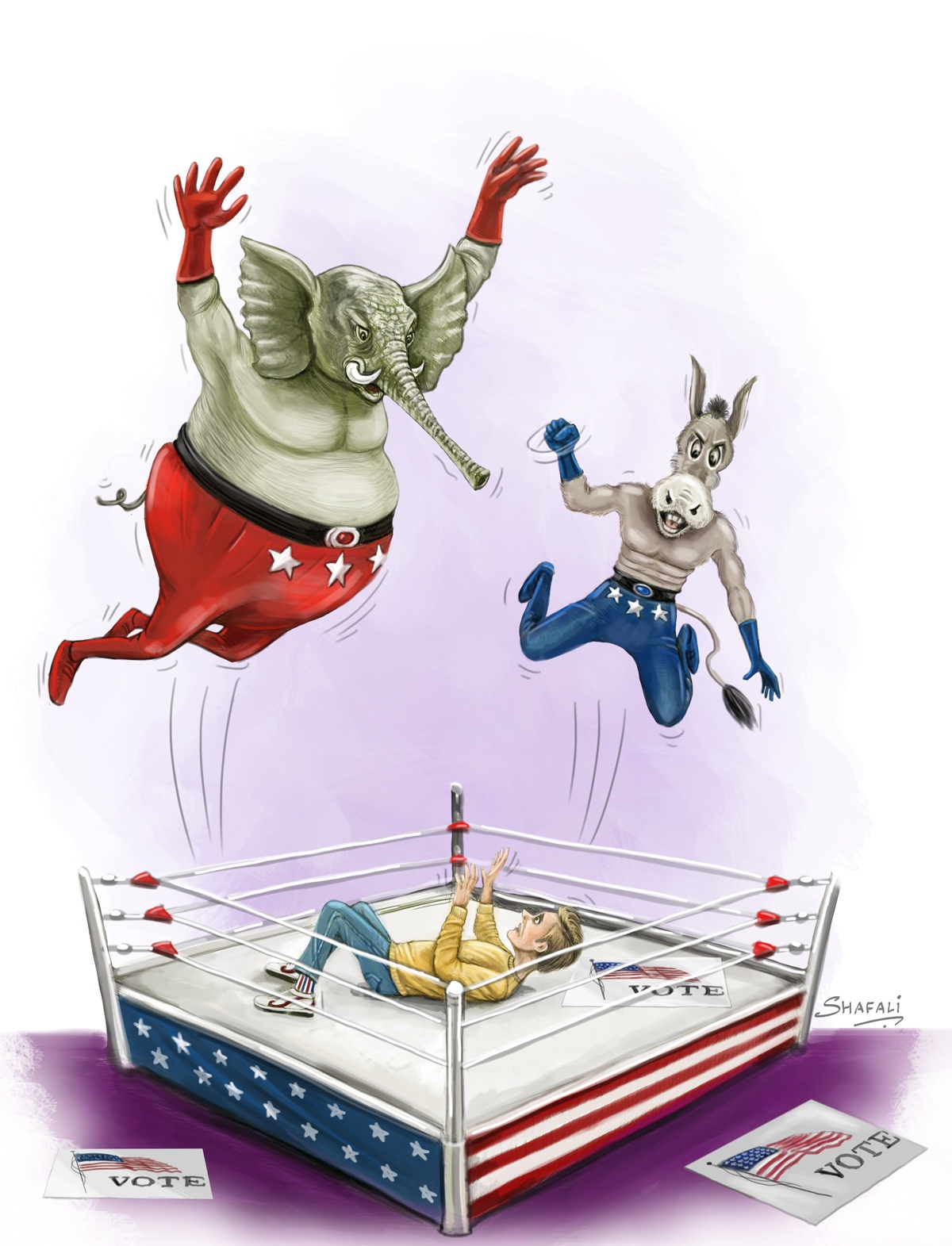

Another election year brings its own questions

by January 5, 2016 12:01 pm 808 views

Editor’s note: The author of this article is a regular columnist for the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

As we embark on another big election year, three questions dominate the specific Arkansas experience.

One – Now that we have moved our primaries to March 1, ostensibly to accommodate the presidential campaign of former Gov. Mike Huckabee, will Huckabee remain a viable or even active candidate by March 1?

Two – For all the worry about pragmatically prone Republican state legislators getting opposed and unseated by more conservative Tea Party-style challengers in the primary – challengers who would be funded by Koch brothers’ groups or the even-more-conservative Conduit for Commerce – do those challenges really pose pervasive threats, or even much exist?

Three – Whither the Arkansas Democrats? Can they still compete much – if at all – outside a few liberal wards and the black community, and, if so, by what tactics and messages?

So to dispense first with perhaps the least consequential of those questions: Huckabee remains formally endorsed by most of the state Republican Party’s establishment – as a courtesy, mostly, as well as a convenience for someone like Gov. Asa Hutchinson who didn’t want to be bothered with having to endorse someone else.

But a state Republican political consultant, speaking not for attribution, says most of those establishment figures – including all the state constitutional officers and all of the Washington delegation except for U.S. Sen. Tom Cotton – have begun to look for alternatives.

“Huckabee has to win Iowa to stay in the race,” the consultant says.

CAN HUCKABEE WIN ARKANSAS?

Polls show Huckabee scraping the bottom nationally and in Iowa, where he won in 2008. But Huckabee’s contention is that polls engage people who answer telephones, not people so engaged and motivated as to venture out on a cold, snowy night in Iowa to stand in a caucus for a candidate.

The evangelicals of Iowa stood for him in Iowa in ’08, and for Rick Santorum in 2012. Thus they sustained for a while, if for only a while, these two religion-based candidacies.

This time Iowa evangelicals seem – from the polls, at least – to be favoring Ben Carson and Ted Cruz and, maybe, even Donald Trump to an extent.

Actually, the emerging question for Arkansas on March 1 regarding Huckabee is two-fold: Beyond whether he will remain active or viable by March 1, it is whether he would necessarily win the state even if still in the race.

Most likely the goodwill toward him among the state’s Republican establishment would net him a courtesy plurality, most agree.

His main rival in Arkansas seems to be Cruz, whom Huckabee’s advisors have long identified as the former governor’s chief competition for evangelicals and arch-conservative outsiders. But there also is evident support in Arkansas for Trump, Carson and Marco Rubio, the latter of whom employs longtime Arkansas Republican operative Clint Reed – a partner in the Impact Management firm of Little Rock – as a key operative in Iowa.

CLASSIC EXAMPLES

Now to the second question about Republican legislators walking around with a dark cloud over their heads, which goes much like this: If these Republican legislators cast a vote they know to be right or best or the most reasonable of bad choices, such as to endorse the private option form of Medicaid expansion or direct additional funding to the highway system, then they risk opposition in primaries from arch-conservative forces who don’t countenance going along with government-as-usual and who will brand them, crazy as it might seem, liberal.

That actual circumstance has arisen only scarcely, which is not to say the scarce occurrences aren’t interesting.

In this year’s GOP primary, there are perhaps a dozen cases of contested primaries pitting really conservative Republicans against really, really conservative Republicans – that being the nature of the choice.

But the specific scenario of a sitting Republican legislator casting a conspicuous vote for the private option and then drawing worrisome primary opposition because of that vote actually exists on this year’s ballot in only two cases.

Both instances can be found in the 35-member state Senate, and both are rather classic examples.

The private option exists because, in the fiscal session of 2014, state Sen. Jane English of North Little Rock cast the clinching 27th vote, locking down the essential three-fourths majority, after she extracted a major policy concession regarding her special interest – vocational education and training.

She’d long argued that the state’s vocational education program was incoherent and ineffective. So when told by leading Republican state legislators and then-Gov. Mike Beebe that they would impose some of her reforms if she would vote for the private option, she decided to go along – only because, by her reckoning, Medicaid recipients would be given better job-training services to enhance their chances of getting off the private option.

OPPOSING ENGLISH

So now comes first-term state Rep. Donnie Copeland of North Little Rock, an arch-conservative preacher and private option detester, to oppose English’s re-nomination for the Senate. He says it’s because of that vote, or, more precisely, because English got elected promising to oppose Obamacare and then didn’t keep that promise.

She was “elected on one guise, one ideology, and then didn’t follow through,” Copeland says.

As Copeland sees it, English traded her vote to expand government by extracting a “pet” project.

She actually made a trade for a “pet” project not in the rawest political sense, meaning for a specific favor for her district or for specific money for state installation or local capital improvement. Instead she traded for a statewide policy she had long believed in.

Copeland’s first campaign finance report showed a long list of maximum personal contributions from family members and associations of Joe Maynard, a businessman in Fayetteville who founded a network of nonprofit conservative organizations – primarily known as Conduit for Commerce – that opposes expanded government and is notable for being even less tolerant of government programs than the Koch brothers’ Americans for Prosperity.

It seems unfair, Copeland says, to make something of that, when Conduit for Commerce is “not seeking anything other than a policy it believes in, and Jane is getting money from groups and health-care providers who stand to benefit financially from expanded Medicaid.”

The other classic example is a primary challenge to state Sen. Eddie Joe Williams, former mayor of Cabot and a consistent private option supporter. Earlier rumors had state Rep. Joe Farrer of Jacksonville, an outspoken private option opponent, thinking of making the race against Williams. In the end, a conservative quorum court member in Lonoke – auto salvage businessman R. D. Hopper of Cabot – filed against Williams.

Gov. Asa Hutchinson, taking sides for the incumbent pragmatists against the challenges from the right, has endorsed both English and Williams.

NOW TO THE DEMOCRATS

Finally, to the question about the relative ineptitude of the state Democratic Party in the wreckage of the anti-Obama Republican revolution since 2010: The answer seems to be that the Democrats are rather substantially inept.

Democrats could muster only a token candidate in only one of the four congressional districts – in Dianne Curry in opposition to Congressman French Hill in the Second District of Central Arkansas. The other three Republicans got a free pass except from Libertarians, who managed to do what Democrats could not and produce ballot presences.

In the state House of Representatives, no one on either side expects significant change in the current Republican advantage of 64-35. Democrats point out that three of those 35 are now open seats, meaning, by their account, they are only defending 32 seats, not 35.

That doesn’t sound particularly confident.

Most projections are that Democrats are at mild risk of dipping below 30 seats in the House; could get close to 40 seats by an optimistic view that would restore some viability, and, most likely, will wind up between 30 and 40 and closer to 30.

Democrats tout as their best prospects for actual gains: Copeland’s abandoned seat in North Little Rock, being sought by two Democrats and a Republican; Richard Wright, an attorney in Arkadelphia challenging state Rep. Richard Womack; Nate Looney, a young Jonesboro lawyer and supposed rising Democrat who is challenging a Republican incumbent, Brandt Smith, who won a relatively close race amid the GOP sweep of 2014; and Dorothy Hall of Sheridan, who narrowly lost a Democratic primary two years ago to Mike Holcomb of Pine Bluff, who subsequently got elected and then switched to the Republicans.

In all cases, the Democratic candidates present themselves as more honorable. They stress that they would go to Little Rock to take care of constituents, not venture into divisive national issues, which, of course, are devastating to Democrats in Arkansas.

On the Senate side, there seems to be little to no chance for the Republicans’ 24-11 advantage to be disturbed. The fun is in those aforementioned Republican primaries for English and Williams.

One Democratic state senator, Bobby Pierce of Sheridan, has potentially serious competition in Republican Trent Garner of El Dorado.

EMERGENCE OF ELDRIDGE

The year’s marquee Democratic candidacy is the one for the U.S. Senate by a preppy 38-year-old former U.S. attorney, Conner Eldridge.

He’s a Davidson College graduate who hails from eastern Arkansas but has spent his recent adulthood in the western part of the state. He formerly worked as a staff aide to Blanche Lincoln and Marion Berry.

He says he’s running for the Senate because he wants to make a difference and you can’t do that in the House.

He has distinguished himself, and left the Democratic base uninspired, by staking out rightward positions on Obamacare, Planned Parenthood and Syrian refugees. But in a recent interview he worked hard to make a case that he is different from the amiably nondescript Republican incumbent – U. S. Sen. John Boozman.

Eldridge stressed that he wanted to improve the Affordable Care Act, not repeal it; de-fund Planned Parenthood only if assured of replacement reproductive health services for women; and not end altogether the nation’s acceptance of Syrian refugees.

Beyond that, he says he supports a path to legal status for illegal immigrants, the hate crimes law and a “live and let live” attitude on social policy, including advocacy for protections against employment discrimination on account of sexual orientation.

FAMILIAR FORMULA

Eldridge says he’s “old school meets new school,” meaning a Democrat in the Arkansas tradition of populist conservatism but new in that Arkansas voters are sicker than ever of politics as usual, which he says Boozman practices on a straight-line party basis, but that he will not embrace on the Democratic side.

A source says Eldridge seems convinced he can compete if he can lock down Democrats and neutralize and win over some Republicans.

The problem for him is that the formula is not new. It worked for years for Democrats in Arkansas, but seemed to lose validity about 2010 with the state’s strong backlash against Obama and the transformation of media and politics in Arkansas in a way that made politics about generic national issues rather than peculiar in-state ones.

Even so, there is speculation among Democratic insiders that Eldridge conceivably could creep to the mid-40s – with Hillary Clinton, not Obama, on the ballot – and, by that relatively decent showing, set himself up as a key player in the state Democratic Party’s future should the Republican takeover begin to lose its stranglehold.

For the current year, though, all reasonable indications are that the stranglehold will remain firm.

Reports both of serious intraparty Republican division and continued Democratic vibrancy appear to have been overly worrisome in one case and overly wishful in the other.