Scientists push EPA to update meat packer wastewater discharge rules

by May 20, 2024 3:08 pm 798 views

A report from the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) alleges that water pollutants discharged from Tyson Foods’ processing plants “pose a risk to people and the environment and include large amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus.”

According to the report, the agriculture industry is the largest consumer of freshwater and meat and poultry processors account for nearly one-third of that water consumption. Tyson Foods is the largest meat company in the country with 123 processing facilities and all that animal processing creates massive amounts of wastewater.

Researchers Omanjana Goswami and Stacy Woods published “Waste Deep” on April 30. While the report notes Tyson Foods is acting within the legal limits, Woods said the regulatory standards for wastewater discharged to surface waters and municipal sewage treatment plants have not been updated in 20 years.

There is a proposed rule change being debated by industry and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The EPA has held three public meetings to discuss the proposed rule changes based on the latest scientific evidence with the public comment period ending March 25. The EPA said it recognizes that meat and poultry production accounts for one of the largest sources of industrial pollution, and nutrient pollution emitted from the plants is a significant environmental challenge that can harm ecosystems and communities.

Tyson and its poultry and meat processing competitors typically discharge pollutants into natural waterways or municipal wastewater treatment facilities. The EPA said this includes pollutants like oil, grease, salt and significant quantities of nitrogen and phosphorus which can deplete oxygen levels with marine life and cause algal blooms that can be toxic to animals – including livestock – or humans.

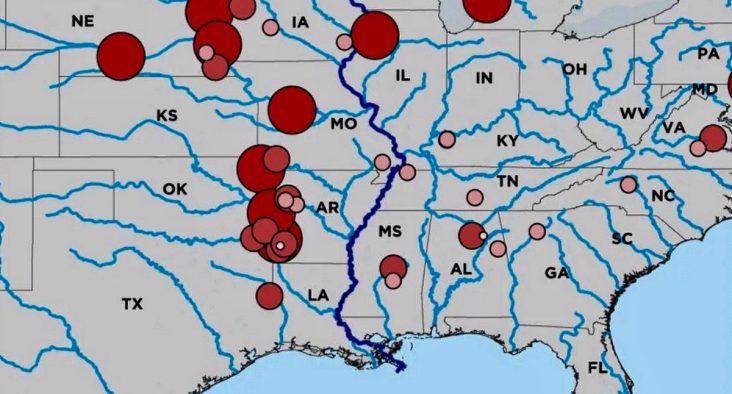

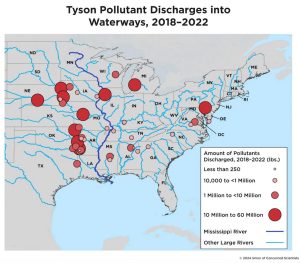

The UCS report looked specifically at Tyson Foods and the wastewater discharges between 2018 and 2022, the last date for which data is available. The Springdale-based meat giant released more than 371.1 million pounds of pollutants into U.S. waterways in that five-year period. UCS reports over half of the pollutants were dumped into water, including streams, rivers, lakes and wetlands, in just three states – Illinois, Missouri, and Nebraska, Illinois. The report noted that all discharges were within legal limits under present guidelines.

Goswami said the UCS analysis is a conservative accounting of the wastewater pollution released by Tyson plants, through activities like animal washing, cleaning meat and animal products, sanitizing equipment and scrubbing work areas. The study looked at the corporation’s 41 slaughterhouses and large processing plants wastewater discharges. Those facilities account for one-third of Tyson plants.

Goswami said Tyson plants discharged over 18.5 billion gallons of wastewater during the five-year period, enough to fill more than 37,000 Olympic swimming pools. She said pollution from plants in the Midwest can travel through the Mississippi watershed and end up in the Gulf of Mexico, feeding a massive and persistent dead zones (areas with reduced levels of oxygen) nearly the size of Puerto Rico. Arkansas waterways received over 10% of reported pollution from Tyson plants, or more than 37 million pounds.

Some of the biggest areas of concern in Arkansas include Scranton where an animal food plant discharged more than 743,748 pounds of pollutants into waterways between 2018 and 2022. A Tyson chicken plant in Dardanelle discharged 857,428 pounds of pollutants into waterways in the same five-year period.

In southern Arkansas, a Tyson chicken plant in Grannis dumped 1.543 million pounds of pollutants in the five-year period. A Tyson plant in Nashville, Ark., had the largest discharge of pollutants at 13.93 million pounds. A chicken plant in Hope, Ark., discharged 1.524 million pounds of pollutants.

The UCS is not the only group calling for more stringent guidelines.

“EPA’s preference for weak slaughterhouse regulations privileges the health of a polluting industry over that of frontline communities and our nation’s waters. To adopt anything less than the most stringent clean water protections in the agency’s final rule would be a missed opportunity and a big mistake,” said Food & Water Watch attorney Dani Replogle.

Environmental Integrity Project attorney Sarah Kula applauded the EPA for “finally taking action” to strengthen standards for some of the largest plants, noting that the meat and poultry industry has benefited from lax water pollution standards for years. She said the EPA must require plants install modern water pollution controls.

TYSON, INDUSTRY RESPONSE

Tyson Foods did not respond to a request for comment, and instead deferred to statements from trade groups.

The American Association of Meat Processors (AAMP) opposes the proposed EPA rule saying the cost for plants to comply could range between 1% to 3% of a plant’s revenue. The unpredictable cost of technology implementation needed for compliance could put as many as 50 plants out of business, according to Chris Young, AAMP executive director. He urged the EPA to work with industry to reduce pollution in a sustainable fashion.

The U.S Poultry & Egg Association said the rule changes could have an overwhelming impact on the poultry and meat industries’ ability to continue providing economical sources of protein to consumers. The group said it has worked with the EPA since early 2020 to facilitate data collection, understand industry treatment capabilities and understand the relationship poultry companies have with their wastewater treatment plants.

The Meat and Poultry Products Industry Coalition estimates the EPA’s wastewater guidelines true cost is over $1 billion and could result in the loss of more than 100,000 industry jobs. The coalition includes the U.S. Poultry & Egg Association, the Meat Institute, North American Renderers Association, National Chicken Council, National Pork Producers Council, National Turkey Federation, and the American Farm Bureau Federation.