Insiders reflect on Walmart turning 60

by July 19, 2022 10:54 am 4,618 views

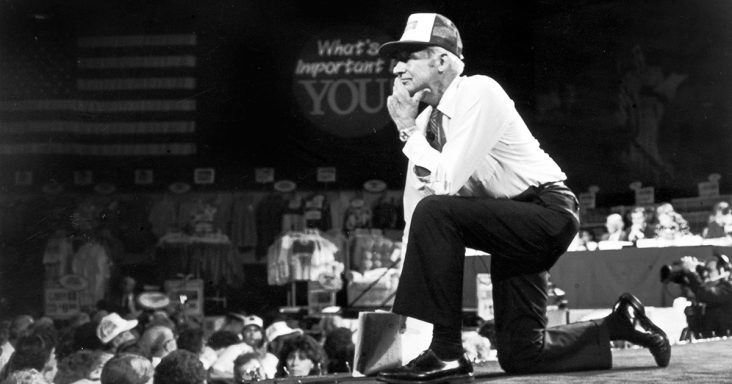

Walmart founder Sam Walton opened his first store in 1962 in Rogers. The company has grown to become the largest retailer in the world.

When 44-year-old Sam Walton opened the first Walmart in July 1962, the economy was recovering from a recession. Unemployment was high, as were taxes. But that did not stop the retail visionary from rolling the dice on a new discount format aimed at offering low prices and making the margin on higher volume sales.

In his memoir, “Sam Walton: Made in America,” Walton said that by 1962 he was convinced the discount idea was the future. Walton had been experimenting, innovating and expanding his retail operation since the early 1940s through various partnerships and running Ben Franklin “five and dime” stores, first in Newport before moving his family to Bentonville in 1950.

Seeking to partner again with discount formats of the time, Walton pitched a franchise deal with Butler Bros. in Chicago and then again with Herb Gibson, who was already franchising as many stores as he wanted. Walton said there were just two choices left: stay in the “five and dime” business he was already running and get hit hard by the discounting wave or try and open a discount store of his own. He set his sights on Rogers because it was a bit larger than Bentonville. But there was already a Ben Franklin store in town, and the owner Max Russell was not interested in a partnership to build a bigger store.

Walton gambled and built the first Walmart in Rogers, saying it was a big commitment from his family at the time and challenged him to find inventory as the store could not use any Ben Franklin items. He said early investors also were hard to find. Walton’s brother Bud put up 3% toward the cost of the store. Don Whitaker, a new hire from TG&Y in Abilene, Texas, put in 2%, and Walton said he put up 95% of the funds. Helen Walton, his wife, also went on the bank notes so he could borrow more money to make the store a go.

“We pledged houses, property and everything we had,” Walton said in the memoir.

Bob Bogle, the first manager at the Walton’s 5&10 in Bentonville, suggested the new discount store should bear the name W-A-L-M-A-R-T, as it included part of the Walton name and indicated a place to shop. But perhaps the most significant selling point was it was seven letters to buy and a cheaper option than the three or four-word choices being considered.

Walmart Store No. 1 was just 35,000 square feet and mostly self-service. Stocking the store also was a challenge as Walton had to source from a distributor in Missouri and buy from wholesalers traveling around the country. He tried to go straight to manufacturers to work out a deal but said no one wanted to work with a retailer with just one store.

By Walton’s account, Store No. 1 wasn’t all that great. But at $1 million a year in sales, it was more than $200,000 to $300,000 the smaller variety of stores of his were doing. He said Butler Bros. was doing about $2 million in sales per store, and it became apparent he needed to add stores. Walmart set its sights on Springdale and Harrison, larger and smaller towns than Rogers, to see how the format would fare.

Claude Harris, an early partner of Walton’s who ran the Ben Franklin store in Springdale, told the Northwest Arkansas Business Journal he first met Sam Walton in 1960 when he was working at Woolworths in Memphis, Tenn., a major department store at the time. He said the meeting was by chance as Walton had come to the store looking for someone else. Harris joined up with Walton and moved to Springdale.

Harris, 92, remembers the first few Walmart locations had their challenges, but that didn’t stop Walton from wanting more stores. Within a couple of years, Harris took a job as the first buyer for Walmart’s operations. He said he had turned down store manager positions at several locations because he was a merchant and didn’t want to manage a store. Harris set out to standardize the buying process across the growing store footprint, which now included Siloam Springs, Conway and Little Rock.

“Once our store count grew, we could leverage the economies of scale and get better pricing, which we could pass along in low prices, which Sam insisted upon,” Harris said. “I set up the departments like those at Woolworths, starting with department one candy and department two health and beauty aids. I then began buying merchandise directly for the stores.”

Harris said Walton told him to get the lowest price, which he did. He said suppliers like Procter & Gamble would come by his office offering specials, for instance, toothbrushes for $1.17. Harris said he had to get a lower price because his competitors would sell for that.

“I insisted on 97 cents, and when the supplier went to Sam, he backed me 100%,” Harris said.

Harris spent 20 years at Walmart and reported directly to Walton. Just before Walton opened his first Sam’s Club in 1982, he asked Harris to look over the club inventory and make suggestions, which he was happy to do.

“We didn’t want Sam’s to compete with Walmart, so we looked for more upscale products like fine jewelry and higher-grade items sold at a value,” Harris said.

MENTOR, TEACHER

Jimm Larry Hendren, a retired U.S. District Court Judge in the Western District of Arkansas, was Walton’s long-time tennis partner and friend who was more than 20 years his senior when the two met in 1965. Hendren was practicing law on the Bentonville square at the time and looking to play tennis.

Hendren remembers there being plenty of skepticism around the first Walmart and fears that discounted items were somehow inferior in quality. But that skepticism was soon squelched when the company added more locations in neighboring towns.

“Sam loved to play tennis. It was one of his passions, as was quail hunting, retail, his Lord and his family,” Hendren said.

At the height of their tennis partnership of 27 years, Hendren said they played three times a day: at 6 a.m., noon, and 5:30 p.m. after work. He said they played most of the games on Walton’s home court. Hendren stood 6’5” tall and weighed 215 pounds, a former minor league baseball player and overall athlete. Walton was 44 and in great shape, as Hendren remembers it. He said Walton liked to win and did most of the time as he focused intensely on his competition, looking for any opportunity to score by exposing the opponent’s weakness. But he quickly added that Walton was also a gracious loser and about improving those around him.

“I have never known anyone else who did not need others to know who and what he was, but Sam was so comfortable in his own skin,” Hendren said. “He would introduce himself and then want to know more about you. He did not need to toot his own horn or even have a horn.”

He said Walton’s eye for hiring talent and his impeccable judging of people’s character served Walmart well in its first decade or so. While Walton was a perpetual student of retail, he also knew more minds were better than one.

“His M.O. was to focus on making those around him better. He expected those around him to rise to the occasion needed, and they did. He was a catalytic guy,” Hendren said.

He said no one worked harder than Walton as he was a constant student of retail. Hendren flew with Walton on numerous occasions to events and tennis matches. Hendren said it was nothing for Walton to fly over stores and count the cars on a Saturday to see how busy they were. He also visited his competition regularly with a yellow pad and pen in hand, asking questions and trying to learn about the operations.

Hendren, who recently a published a book titled “Sam Stories” about his friendship with the Walmart founder, said Walton was a mentor and teacher of many in retail and beyond, including himself. While Hendren professed he and Walton did not talk a lot about the business, he believes Sam and Helen set a strong foundation for Walmart in its core values to operate leanly to provide what people needed at a fair price so they could enjoy a good life.

WHAT WOULD SAM THINK?

Walton ran Walmart for its first 30 years and saw the company he built grow to $43 billion in revenue by 1992. Supercenters had been around for four years when Walton died, and there were 1,720 stores and 208 Sam’s Clubs.

In the 30 years since Walton died, Walmart has had its ups and downs amid a rapidly changing world. But the retail giant recorded more than $572 billion in revenue last year from 10,800 stores across the globe. That’s big enough to make it the largest retailer in the world.

Harris said if Sam were to walk into a Supercenter today, he would be in awe. He believes the stores are run well, and Sam would be OK with the services provided if that’s what the customers wanted. The same goes for the growing online business.

Hendren agreed that Sam would also likely smile about Walmart’s efforts to buy more products made in America, as that was his goal early on. He said one of Sam’s best attributes was his ability to listen, and he would be glad to see management listening to customers today. He said Sam’s billions did not change the man he was nor his genuine concern for others.

Walmart President and CEO Doug McMillon told the Northwest Arkansas Business Journal he often dreams about seeing Sam in heaven and talking with him about what has gone right and what could have been done better.

“I think he would first want to know about associates, and he would be excited about what they have accomplished,” McMillon said. “He would want to know how they were feeling. He would want to know what we’re doing to help customers with these rising prices. Are we challenging suppliers to help, or could we partner with them in a different way to get prices lower? He would be excited about what we are doing as a regenerative company. Sam loved nature and the outdoors and would support the sustainability efforts.”

He said Sam would likely have questions about the new business model, asking what it means. He would be curious about the $2 billion in ad sales and Walmart Connect and want to know exactly how it worked and who it all helped.

McMillon has previously said Sam and the early management team left Walmart with a strong set of values and one single mission that has stood the test of time: to help people save money so they can live better. But equally important to Walmart’s future, he said, is the “swim upstream” philosophy and risk-taking appetite, which is also part of Walmart’s DNA.