An obligation to speak: Holocaust survivor details concentration camp experience

by December 12, 2021 12:44 pm 2,873 views

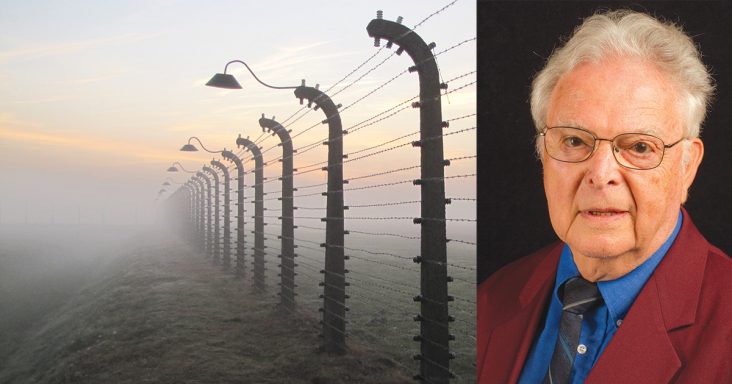

Holocaust survivor Steven Fenves.

Steven Fenves was an avid stamp collector. The Jewish boy, living in Yugoslavia during the 1930s, spent hours on his collection of stamps. When his country was invaded at the onset of World War II, his parents lost their income and they had to barter whatever possessions the family had for food.

“My mother had to sell my stamp collection,” Fenves said.

He was the featured speaker at Black River Technical College’s 15th annual Holocaust Survivor’s Series held in late October.

Fenves was born June 6, 1931, in Subotica, Yugoslavia, a town of 100,000 inhabitants with a Jewish population of nearly 6,000. His father, Lajos, managed a publishing house that included the main Jewish newspaper in the region and his mother, Klári (Klara), was a graphic artist. Although they studied Serbian in school, Steven and his elder sister, Estera (Eszti), spoke Hungarian and German at home.

Fenves said he had a typical upper-middle class upbringing. His family had a maid, cook, and even a chauffeur. He said the region was poor, and if you bought a car it was considered poor taste to not employ someone as a driver. That world was shattered soon after the start of World War II began.

The Axis invaded Yugoslavia on April 6, 1941, and five days later, Subotica fell under Hungarian occupation. On the first day of the occupation, his father was forced from his office at gunpoint and his business was handed over to a non-Jew, a process referred to as “Aryanization.” Klári knitted shawls and the family had to sell all of their possessions. Until May 1944, the Fenveses lived in one corner of their apartment, while Hungarian officers took over the rest of the family’s home.

In March 1944, Germany occupied Hungary and Hungarian-occupied Yugoslavia. In April, Lajos was deported to Auschwitz concentration camp. Fenves, his sister, mother, and maternal grandmother were forced into the ghetto in Subotica in May. He worked as a machinist outside the ghetto, one of the few who had a pass to leave. On his 13th birthday, he was the first in the ghetto to learn of the Allied invasion, and when he returned home that night, he informed the rest of the people in the ghetto.

Hope was restored by the invasion, but it would end days later.

On June 16, 1944, the Subotica Jews were rounded up and sent to the nearby transit camp of Bácsalmás where they remained for 10 days before being deported to Auschwitz. The family was locked in cattle cars with no food or water for five days on their way to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Unlike the depiction in the movie “Schindler’s List,” there was no platform when they arrived.

“You had to jump out or be thrown out of the cars,” he said.

It was here they saw German soldiers for the first time. All the atrocities and round up that occurred up to this point had been done by the Hungarians, he said. During “processing” he noticed doctors inspecting Jews. He was told that one of them was Dr. Josef Mengele, often referred to as “The Angel of Death” because of the horrifying experiments he conducted on live humans.

Fenves, Estera, and Klári were selected for work, but his grandmother was not.

“My grandmother went nowhere. … She just sat there waiting to be taken to the gas chamber.”

No food or water was given to them. The stench of burning bones and flesh, and the abject filth was unbearable and he still can remember it to this day. All of his body hair was shaved off and he was forced to take a cold shower. He was given a tattered camp uniform to wear. Food was served once a day in a barrel used by everyone in the barracks, and only one restroom break per day was allowed. Toilet paper was replaced with smooth rocks if you could find one on the way to the latrine, he added.

Klári perished a few weeks later.

The barracks were supervised by German Kapos, or overseers, and because he spoke fluent German, he was chosen to be an interpreter. Eventually Polish political prisoners took over the supervision of the barracks. One of them made Steven his interpreter and, with his knowledge of Serbian, Steven quickly became fluent in Polish. He became part of the Birkenau resistance, working on a roof repair detail that went from compound to compound, smuggling lists of prisoners and trading black market goods. He met his sister and was able to bring her a scarf and sweater, bartered on the black market, before she was sent on a transport to another camp.

In October 1944, Fenves was smuggled out on a transport to Niederorschel, a satellite camp of Buchenwald, where he spent nearly six months working on the assembly line in a junkers’ aircraft factory. On the night of April 1, 1945, the inmates were led out on a death march; they entered Buchenwald late on April 10. After being herded into one of the barracks, Fenves went to sleep. The next morning the camp was liberated by American soldiers from the 6th Armored Division.

He returned home to Yugoslavia where he was reunited with his father and sister, but his father died a few months later. Fenves returned to school where he was forced to join a communist youth organization or risk expulsion. He and Estera decided to leave Yugoslavia and in 1947 they escaped to Paris. After three years, they immigrated to the United States, settling in Chicago. He was drafted into the U.S. Army 18 months later. After he was discharged, he studied on the GI Bill, eventually earning his doctorate.

Ironically, there were four Hungarian newspapers in the U.S. when he arrived. Three of them were run by editors who had worked for Fenves’ father.

Fenves entered the computing field in the mid-1950s and devoted his 42-year academic career, at the University of Illinois and later at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, to the development of computer concepts and tools for civil engineers. Fenves retired in 2009. He and his wife, Norma, live in Rockville, Md. He is a volunteer at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Why does he keep speaking out?

“As a witness and survivor, I have an obligation to do this … for the millions who didn’t survive,” he said. “I have an obligation to let the world know what happened.”