Mote recalls role guarding Little Rock Nine during crisis at Central High

by October 25, 2018 5:47 pm 1,815 views

Jim Mote, a retired investment adviser, once served as a military guard during the 1957 Little Rock Central High School crisis.

Jim Mote was an 18-year-old farm boy picking cotton in northeast Arkansas one morning when he saw a military truck approaching. It was September 1957, and Mote — one of nine children in a sharecropping family — was in a cotton patch east of Jonesboro.

It was a rural area, and like most small school districts at the time, Monette High School operated on a split term. That meant classes were dismissed in September and October so students could help pick cotton. Mote’s high school basketball coach — Bill Bishop, who was later elected to the Arkansas State Senate in 1970 — doubled as company commander of the Arkansas National Guard unit in Jonesboro.

“As soon as we turned 17, he had us all join,” Mote recalled. So, his curiosity was piqued more than usual when he saw the three-quarter ton truck approaching.

“I wondered what was going on, of course,” Mote said. “When [the truck] got to where we were, I recognized my section sergeant up in the truck. So I went to meet him. “He just told me, ‘Come on. We’ve gotta go.’”

And with those orders, Mote was on his way toward his role in American history. Mote’s Arkansas National Guard unit was ordered to Little Rock by Gov. Orval Faubus to assist in the desegregation crisis unfolding at Central High School.

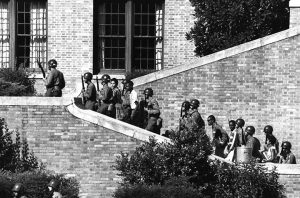

Mote is now 79, long retired from his career as an Army reserve officer, and recently retired from a 30-plus-year career as an investment adviser in Rogers. During a recent interview at WealthPath Investment Advisors, the company he helped launch in 2011, Mote recalled in detail his job in 1957 that evolved from crowd control to eventually protecting the Little Rock Nine. He was one of 18 armed escorts chosen to accompany the nine African-American students into all-white Central High School and remain with them wherever they went throughout the school day. He did that for two weeks.

“Gloria Ray was the last one off the bus, and she is the one we were assigned to,” Mote said of the first day, Sept. 25. “We had fixed bayonets, a .45 [caliber] pistol on our hip and carried nightsticks.”

‘IT WAS HORRIBLE’

Mote said he still remembers the hard benches on the 2.5-ton military truck during the nighttime ride from Jonesboro to Camp Robinson in Little Rock. He didn’t know a lot about the situation that awaited at Central High, and had hardly any exposure to African-Americans in northeast Arkansas. He was taught by his parents, though, that you didn’t say derogatory things or belittle people.

Mote and others in the company who were chosen to be escorts prepared specifically for the job before they were deployed on campus. This was after President Dwight Eisenhower federalized the entire Arkansas National Guard. Eisenhower also sent 1,000 members of the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division to Little Rock to override Faubus’ decision to use state troops to surround Central High School and prevent federally mandated integration.

Mote said that during the first class of the first day the African-American students were admitted, the teacher calling roll did not acknowledge Ray’s presence. That was the pattern most of the morning, he said, and Ray ate alone in the cafeteria.

“It was horrible. I hurt for her,” Mote said. “She was timid.”

Mote said Ray’s first class in the afternoon was geometry, and the teacher was a young woman in her late 20s.

“She called the roll, and after she called everybody else, she said, ‘Miss Gloria Ray,'” Mote recalled.

“Present,” Ray responded, barely above a whisper, Mote said.

“Welcome to my class,” the teacher responded, smiling.

“The other students started hissing and disapproving and making sounds, and of course we couldn’t do anything,” Mote said. “We were just there. But I have always remembered that.”

Mote said the white Central High School students would call him names and “catcall” him and the other troops. But he only had one incident with a student during the two weeks with Ray.

After a month’s time in Little Rock, the high school students in the Arkansas National Guard were released from duty and allowed, if they chose, to return home. Mote did and didn’t see Ray again until he attended a 50-year commemoration event of the segregation crisis in 2007.

“She remembered that we were with her, and that was neat,” he said.

AFTER THE CRISIS

With his role in the Central High School crisis behind him, Mote graduated from Monette High School in 1958, then accepted an athletic scholarship from the University of Arkansas to play basketball and run track for the Razorbacks. He also participated in the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps program at the UA, graduating in December 1963 with a physical education degree.

He accepted a two-year commission as an Army Reserve Officer and reported to Fort Benning, Ga., eventually becoming company commander. Just before his commission was up, Mote and other reserves were being recruited to remain in the military.

“This West Point major had come down and had my records. And he said, ‘Mote, you’ve got a great record here, and if you applied for a regular Army commission, you will have no problem getting it.”

That would have ultimately led to a deployment in Vietnam.

“If you want to be a career officer, you want to go to Vietnam,” the officer explained to Mote. “You want that combat experience.”

With a young wife and a newborn less than a month old, Mote declined.

“I really did like the military, though,” he said.

BACK TO ARKANSAS

After his military duty ended, Mote remained in Georgia and began a new career in workforce training that ultimately led him back to Northwest Arkansas. In 1975, he was working for TRW Inc., a diversified maker of high-technology products, when he was dispatched to Columbus, Ga. — his wife Alice’s hometown — to build a training program for the company’s new hand tool plant.

After four years there, the company sent Mote and his family to Rogers to implement training at another of its plants. The company’s name changed over the years several times as corporations merged or were acquired, but that facility is now known as Kennametal, a global supplier of tooling and industrial materials.

When the company sold to The Harbour Group in 1986, Mote pursued other professional interests. He went into the securities business working for Bob Taylor in the Rogers office of A.G. Edwards. That started a long financial services career that developed into a focus of consulting and advising retirement plans, as well as managing individual and family investment portfolios.

“I never considered myself a salesman, and still don’t,” Mote said. “But what I did like was math. It’s a numbers thing. Just pencil to paper and see what you can save.”

Mote worked for several brokerages before his last stop with Jim Edmiaston, Clay Kendall and Erik Berry. They formed WealthPath Investment Advisors seven years ago. The Rogers-based independent wealth management firm has about $460 million in assets under management, with satellite offices in Fayetteville and Little Rock.

“With significantly younger partners, his experience has been invaluable,” said Kendall, who is 43. “I’ve known him for almost 15 years, and he is one of the best mentors I could have asked for.”

Mote, married for 53 years and the father of three, left the firm in January 2017. But he is still a counselor and adviser to his former partners. In retirement, he plays golf regularly in a men’s group at Lost Springs Golf & Athletic Club, but he said adapting to a life without work was not as easy as he’d thought.

“When you’re working, you’ve got a schedule, you know where you’re supposed to be and what you’re supposed to be doing,” he said. “In retirement, I don’t have a schedule, I thought I’d play golf. … I don’t know what I thought. Last year, I was a little bit lost, and it took me a while to adjust.”

Most immediate on Mote’s calendar is a celebratory week in November. He will mark his 80th birthday on Nov. 10, 54th wedding anniversary on Nov. 14 and his wife’s birthday on Nov. 15.

For a farm boy from northeast Arkansas, he said, it has been a good life. One that included a small role in American history.