Eddie Mae Herron Center in northeast Arkansas commemorates black history

by May 21, 2018 2:20 pm 872 views

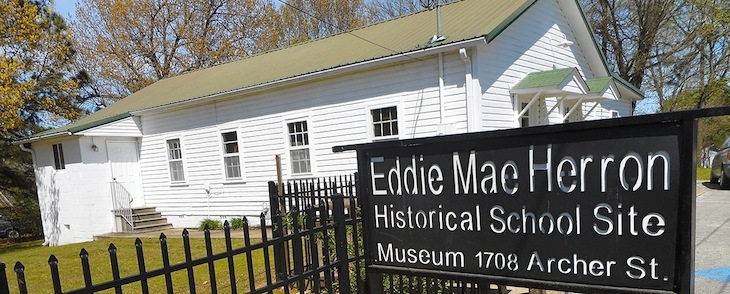

The Eddie Mae Herron Center in Pocahontas.

Inside the Eddie Mae Herron Center in Pocahontas there’s a ticket on display. The ticket was fastened to a piece of property owned in 1826 by T.H. Porter, a horse and slave trader. The ticket was attached to a black male slave he owned.

It is one little piece of history stored at the center that recognizes black history in Randolph County, center co-founder Pat Johnson told Talk Business & Politics. The center was known as the Pocahontas Colored School during segregation and Johnson attended school there starting in 1954. She can’t remember the first time she entered the building, but she never forgot the teacher who transformed her life.

“Mrs. Eddie Mae Herron. She was our teacher. She taught us everything. She taught us how to read, write and how to do math. She was a wonderful person. I admired her very much,” Johnson said.

Several thousand visitors come to the museum each year, according to sign-in rolls. Local school districts send students to the museum to learn about the area’s history. Students take part in activities sponsored by the museum, such as the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. celebration. It’s one element in the tourism dollars generated in the region.

About $22.57 million was spent in the county in 2017 on travel expenditures, according to the Arkansas Tourism Impact Report. Tourism generated $2.95 million in payroll and supported 144 jobs. It produced $1.34 million in state taxes, and $590,167 in local taxes.

Randolph County’s modern history began in 1802 when 17-year-old William Looney left his east Tennessee home with two slaves. He journeyed to the Eleven Point River Valley in present-day Randolph County, according to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Looney decided to settle in the area. It had rich fertile soil, and there are five navigable rivers in the region.

Owning slaves was a common practice in the county pre-Civil War, but Johnson said it’s hard to tabulate how many slaves lived in the county. There are several black cemeteries, including Friendship Cemetery, that date back generations. Many of the headstones are lost, or in such disrepair that names cannot be identified. Some date to the time of slavery, she said. Several of the identifiable tombstones are listed on the museum’s website to aid genealogical research.

After the Civil War, there was a small but vibrant black community in the county, Johnson said. In 1919, a church was built that would become the museum. A deal was struck with the local school district to teach black children at the church, Johnson said. Johnson’s older siblings attended school, and she started going to the school at the age of three. Most kids there were poor, and it was common practice to bring siblings to school even if they weren’t old enough to attend. Once her classes began, Johnson said she entered into a “whirlwind” of learning.

“Mrs. Eddie Mae taught all subjects in grades one through eight,” Johnson said. “I don’t know how she did it. We all loved her.”

After the eighth grade, students were bused from Pocahontas to another segregated school in Newport, more than an hour’s drive one way at that time. One thing that never made sense to Johnson was that on the way to Newport, the bus would pass the Hoxie School District, which had already been desegregated.

“Why didn’t we just go to school there?” she asked rhetorically.

In 2000, Johnson and others began to turn the building into a museum. When it was a school, it got only the hand-me-down books, chairs, desks and other materials from the white school. The reconstructed classroom is a hodge-podge of chairs, desks and other items. A picture of George Washington prominently hangs in the museum. Students said the pledge of allegiance each morning and stared at his picture while doing so. They weren’t given a flag for the pledge, she said.

Racism existed during that period in the county, Johnson said, and she experienced it. A bathroom sign in the museum reads “colored only” and that was a defining theme during her childhood. White kids rarely played with black kids, she said. Johnson said she has chosen not to be bitter about the past, but she wants it to be remembered. Next year will mark the 100-year anniversary since the church and school building was first built, and the museum is planning a celebration, she said.

Many black residents have left the county, mostly for economic reasons, she said. Less than 2% of the county’s population is African-American, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Johnson is hopeful many of the families that came from Randolph County will return to celebrate.

“It has always been a place of education, and it was a place that lifted our spirits,” she said. “I would love for all of us to share that feeling again.”