Randolph County may vote on alcohol sales in November

by April 11, 2018 12:47 pm 1,451 views

A new grassroots organization, Let Randolph County Vote, will attempt to get the question of alcohol sales on the November ballot in Randolph County.

It’s the third attempt since 2014 to allow for a vote on alcohol sales in the dry county, and LRCV Chairwoman Linda Bowlin told Talk Business & Politics those pushing for a vote have learned a lot from past failures.

Arkansas’ law requires 38% of registered voters in a county to sign a petition to allow a wet/dry vote, meaning at least 3,813 voters had to sign in Randolph County in 2016. A different organization, Keep Revenue in Randolph County, spearheaded the effort in 2016, and collected about 6,000 signatures, but only 3,452 were validated by the Randolph County Clerk’s Office. A circuit court suit filed by the proponents challenging the clerk’s finding was unsuccessful.

There were 10,056 registered voters in the county as of mid-March, meaning the group will need to collect roughly the same number of signatures from registered voters as was needed for the previous effort. As of late March the group has collected slightly fewer than 1,000 signatures. The goal is to have at least 4,000 legitimate signatures by early August. There has been no public opposition to the effort, but Bowlin isn’t sure how long that will last.

This election cycle will be different, Bowlin said. If an invalid signature is found on a petition, then state law dictates all signatures on the page be declared invalid, she said. The 40 or more volunteers and paid canvassers are putting only one signature per page, meaning if the signature is struck, it alone will be struck. The organization has held a couple of “drive thru” events at parking lots on heavily traveled areas in Pocahontas to collect signatures, Bowlin said.

“Our process is much more refined and better focused,” she said.

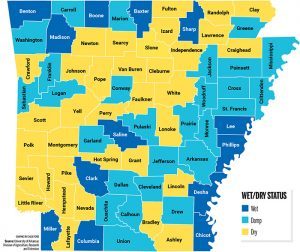

Proponents of the legalization efforts tout the county’s lost revenues as a motivation to drive alcohol sales in the county. A University of Arkansas survey estimated the county would have about $3.3 million in retail alcohol sales each year, and the county and the city of Pocahontas would collect about $107,000 a year in sales tax, combined. It would create at least 19 jobs, and have another $1.3 million in other economic impacts. Randolph County residents now drive to neighboring counties and Missouri to buy alcohol. Two bordering counties, Sharp and Greene, are wet.

If the measure is passed, beer and wine could be sold at grocery stores and convenience stores if the owners choose to do so. The Arkansas Alcoholic Beverage Control Division (ABC) allows for one liquor store per every 5,000 residents meaning the county, with fewer than 20,000 residents, would be allotted three package liquor store licenses, Bowlin said.

The argument that people should vote on the issue has been a good one for proponents this cycle, Bowlin said. It’s hard for voters, even those who oppose alcohol sales, to argue against allowing citizens to decide the issue, she said. There are some whose convictions are so strong they won’t sign the petition. Bowlin said if the issue makes the ballot and the electorate votes it down, she can live with that result. But, she can’t understand not letting it come to a vote.

“It’s very disheartening when someone won’t sign to allow a vote,” she said.

Bowlin understands the uphill struggle her organization faces. Sharp County voted to go wet in 2012 after environmentalist Ruth Reynolds fought for years to bring the issue to a vote. Some liquor outlets in neighboring counties and some local churches opposed the measure, but those efforts failed.

Liquor store owners and religious organizations have fought for years to reduce access to alcohol, Bowlin contends. The sale of alcohol is the only issue in the state that requires 38% of the registered electorate to sign the petition to get it on the ballot, an unheard-of number, she noted.

Opponents’ contentions that voting the county wet will result in bars and honky tonks on every street corner are misguided, she said. Businesses that seek to sell liquor by the drink must go through a strict process with the ABC board, and in Sharp County there wasn’t an increase in night clubs, Bowlin said. There will likely be public opposition, and Bowlin said her group is ready for the fight.

“We just want the right to vote. What’s more American than that?” she said. “It’s a fundamental American procedure to vote. … People in dry counties are being disenfranchised. We should have a vote. The people should decide this issue at the ballot box. The people who turned us dry 70 years ago are gone.”