National Labor Relations Board chair talks to UA law students about changing workplace issues

by November 22, 2016 2:10 pm 368 views

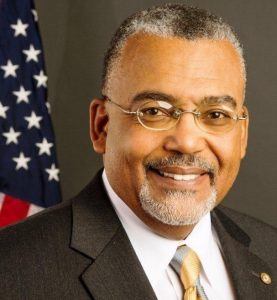

Mark Gaston Pearce, chairman of the National Labor Relations Board, spoke recently in Fayetteville about how the federal agency has adapted to change in its 81-year history of enforcing the National Labor Relations Act.

On Monday (Nov. 21), Pearce discussed the act in front of about 25 people inside the E.J. Ball Courtroom at the University of Arkansas School of Law. In 2011, President Obama named Pearce chairman of the board after he was sworn in as a board member in 2010.

“The National Labor Relations Board protects the rights of most private-sector employees to join together, with or without a union, to improve their wages and working conditions,” according to the agency’s website.

In 1935, the board was designated to enforce the National Labor Relations Act. It was established to “encourage meaningful collective bargaining,” but over the years, collective bargaining stopped getting credit for what’s positive and started getting the blame for what’s wrong, Pearce said. The act was planned to be neutral between employer and employee, but Pearce said it was not. It was established to protect workers. Cynthia Nance, dean emeritus, Nathan G. Gordan law professor and director of pro bono and community services at UA law school, said employees don’t need to be in a union to bargain collectively.

The federal agency operates nationwide with 1,700 employees and has moved from the attic to the kitchen.

It’s given “them a little indigestion,” he joked. “The workplace is one you blink an eye, and you see a different environment.”

The agency resolves 90% of labor disputes before a decision is even issued, and prevents the economy from being disrupted, he said. “We put people back to work” and protect workers’ rights from abuse by both labor unions and employers. He said protects those “struggling to make ends meet, pretty much hand to mouth,” immigrants, single mothers, those who are “too old to start a career or too young to retire” and the tech-savvy, self-absorbed “modern worker.” They might not need to form a union, but they are workers who are talking about their salaries. They might want to write a blog or tweet about workplace conditions.

“We help those folks too,” he said.

As technology changes, so does the modern worker. They are less “brick and mortar and more cyber.” The watercooler or breakroom are no longer places one can talk with co-workers. In his workplace, Pearce said that’s where people go to get away from other employees. Other forms of protected communication includes texting via smartphone and chatting on social media.

One case he mentioned included an employee using Facebook expressing their frustration about a supervisor. The employee used a word that “rhymed with glass bowl,” Pearce said. A co-worker liked the comment, and both were fired.

“But that was protected speech.”

Another case involved a supervisor who was using racial epithets toward employees, and an employee on the receiving end took out his smartphone and colorfully described how his boss had no respect. The supervisor was being discriminatory, and the employee’s action was protected.

In a separate case in which the speech wasn’t protected, a person who had been accepted for a job was inciting insubordination on Facebook. But disloyalty isn’t protected, according to the Supreme Court.

“The employer withdrew the letter of invitation to hire,” Pearce said.

Sometimes it’s difficult to determine whether someone is an employee of a company. In this gig economy, “it’s like playing Where’s Waldo,” he said.

One case involved student-athletes and whether they could negotiate a share of profits from image licensing. The board didn’t take on the case, and “it would have been a mess,” he said. While the board didn’t determine whether the student-athletes were employees, in a separate case, it found students should be considered employees.

The board also protects the 3 million workers who are employed by temporary agencies. In one case, temporary workers wanted a seat at the table along with the company workers to discuss wages. The board agreed they should be allowed to join the company workers to bargain collectively.

Still in dispute in federal court is a case about settling workplace disputes through arbitration. The argument is whether the disputes are handled individually or in a class of employees. The board believes they can be handled in a class of employees, and some courts agree. But the Fifth Circuit, which has jurisdiction in Louisiana, disagreed.

When asked about the legacy of the “Obama board,” he explained how the past several years haven’t been easy with “government shutdowns.” Yet, 2013 was the first time in a decade the board had five members. Pearce’s term on the board runs through August 2018, and he expects to continue to handle labor cases until then. Whether he remains on the board, will be the next president’s decision.

“There’s always going to be a need for us,” he said. But how much the board can flex its muscle “remains to be seen.”

This was Pearce’s first time to Arkansas. He came on invitation of the UA law school and spoke to law students earlier in the day.