Diamond Pipeline project across Arkansas ready to go; some say project is a Flint, Mich., crisis in the making

by August 11, 2016 3:49 pm 1,938 views

Editor’s note: This is the first of two stories about the planned $900 million Diamond Pipeline that will transport crude oil across Arkansas.

––––––––––––––––––

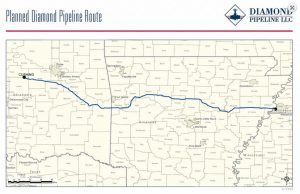

Diamond Pipeline officials are prepared to begin construction on a $900 million, 440-pipeline before the end of 2016 once state utility regulators hold a hearing next week that will close the book on any remaining hurdles for the three-state project.

On Aug. 18 at the Arkansas Public Service Commission headquarters in Little Rock, state utility regulators are scheduled to consider a narrow request by Texas energy giants Plains All American and Valero Corp. on how they plan to construct and operate a crude oil pipeline across several major water sources along a snaking route between the Arkansas River Valley and Ozark Mountains.

It has been exactly two years to the date since Houston pipeline giant Plains All American and Valero Energy, the nation’s largest independent refinery, first announced plans to build the multistate system that will deliver America’s benchmark light, sweet crude oil – West Texas Intermediate – across the heart of Arkansas.

When the project was announced on Aug. 21, 2014, Diamond Pipeline officials said the new supply of top-shelf crude will enhance the long-term viability of Valero’s Memphis refinery, which produces gasoline, diesel and jet fuel for the greater Memphis and eastern Arkansas area. San Antonio refining giant Valero also has thousands of company, Diamond Shamrock, Shamrock, and Beacon-branded retail gasoline stations across the U.S. that will also gain access to another source of high-grade gasoline or diesel fuel that powers most of the vehicles travel the nation’s roads.

Once operational, the pipeline will be able to transport up to 200,000 barrels per day of premium grade crude from the world’s largest petroleum storage facility in Cushing, Okla., east across the Natural State to a Valero’s sprawling 195,000 barrel-per-day refinery in Memphis.

Earlier this summer, the multistate project received a nationwide permit from the U.S. Corp of Engineers, which essentially gave the Texas pipeline joint venture the green light to move forward with the project despite some unanswered eminent domain concerns and fears that a rupture of the system could lead to a disaster similar to ExxonMobil’s Mayflower oil spill in 2013.

SOME SAY PIPELINE ‘FLINT’ CRISIS IN THE MAKING

Despite the PSC’s staff endorsement and support from the Arkansas State Chamber of Commerce, recent docket filings by Clarksville Light and Water Company show that officials in Johnson County are concerned a possible pipeline rupture could permanently damage the area’s watershed. In testimony filed Aug. 4 on behalf of Clarksville Water and Light, Stewart Noland, president of Crist Engineers Inc. in Little Rock, raises the specter of ExxonMobil’s oil spill in Mayflower in 2013 by saying a pipeline rupture in Clarksville could be far worse than the Flint, Mich., water crisis.

“The water utility system in Flint, Michigan, was contaminated by high levels of lead from the water delivery system, but the drinking water supply source itself was not contaminated. Many residents in Flint had available water during the crisis for bathing, washing and other essentials besides drinking,” Noland testified. “Compare this to an oil spill in the Clarksville watershed, which could essentially stop water production altogether. There would be no water available at all to the 28,000 customers of the Clarksville water system, including wholesale and industrial customers. Customers would be left with no water at all for daily activities including drinking water.”

Nolan also argued that a large release of crude oil into the watershed could take months or years to clean up.

“During this time, the water supply would not be available to the Clarksville water system, and a temporary water supply would be needed to supply water,” said the Little Rock engineer. “Even after cleanup of the initial release, it is likely that the residual contamination would cause the Arkansas Department of Health to not approve the watershed for future use as a drinking water supply.”

Noland said the relocation of the proposed pipeline to a location outside of their water supply watershed is the best scenario for Clarksville.

“If the location of the pipeline were to remain the same, the water supply intake would need to be relocated to a location that is upstream of the pipeline if possible,” he said. “If the water supply intake is located upstream of the pipeline location, the water supply would be unaffected in the event of an oil spill.”

Clarksville Mayor Mark Simpson sent a letter in July 2015 to the U.S. Corps of Engineers office in Little Rock to express his concern about the pipeline route.

Rugaard said pipeline owners are committed to safety and have met with Johnson County officials.

“We’re committed to designing, constructing, operating and maintaining the Diamond Pipeline in a safe and reliable manner,” Rugaard said in a statement. “It’s important to us to be a good neighbor, as we hope to have our pipeline in service for years to come. We’ve engaged in discussions with Johnson County community leaders for several months about their concerns, and we hope and expect to reach a mutually agreeable solution.”

FACEBOOK OPPOSITION

Despite the likelihood that construction will begin, a Facebook group in Johnson County has been formed to bring awareness to local fears that the pipeline poses to the area’s watershed in hopes that Arkansas regulators will prevent the pipeline from cross the Arkansas River at Ozark.

“Very few people are aware of this pipeline due to the fact that Arkansas Law does not require them to notify the public or allow public input,” says a statement on Diamond Pipeline and Johnson County Facebook page. “In addition, the Arkansas Constitution gives oil companies eminent domain rights to take landowners property for private use.”

In addition to regular updates and news articles on Diamond Pipeline development and past environmental problems that Plains All America has had on other similar projects, the Facebook page also has posts, photos and videos of local protests against the multistate development. Clarksville City Council member Danna Schneider is somewhat resigned that project construction will soon move through Johnson County. What she hopes is that local efforts will be able to “pause” the development so the public will understand that a future oil spill accident from the pipeline would destroy the region’s most precious natural resource – Ozark water.

Her opposition packet provided to the PSC also includes information reminding commissioners that Plains All American was indicted in 2015 on numerous criminal charges related to an oil spill that sent 143,000 gallons of oil into the Pacific Ocean near Santa Barbara, Calif.

In a phone interview with Talk Business & Politics, Schneider said next week’s hearing before the PSC is essentially the state’s approval of the U.S. Corps of Engineers nationwide permit. She said Diamond Pipeline officials could have quelled any controversy simply by choosing a route for the crude oil line that doesn’t cross the Arkansas River at Ozark.

Schneider, who is responsible for the Johnson County Facebook page, said the city of Clarksville will bring several carloads of people to the PSC meeting in Little Rock next week to bring home that point with state regulators take “a look see” at the development.

“We just want to PSC to slow down the process,” she said. “They (Diamond Pipeline) folks could have taken a straight through Clarksville like most of the other (transmission) projects – but they didn’t. The zig-zag route they chose brings our watershed into danger. We want to protect it.”