John Brummett: Happy hours and high times in Arkansas politics

by March 9, 2016 8:47 am 1,103 views

Editor’s note: The author of this article is a regular columnist for the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.

The New Year’s Day passing of 90-year-old Dale Bumpers set off a flurry of nostalgia about the vibrant political time in Arkansas that gave rise to him.

Tributes to Bumpers and the era he essentially launched inspired Talk Business & Politics to take a look at the 1970s in Arkansas politics.

A decade known nationally for Watergate, disco, bell-bottoms and leisure suits was maybe the most notable in Arkansas political history. It was uncommonly eventful, competitive, reform-spirited, dramatic and transformative. It was rich with a new kind of political talent – young, moderate, well-educated, modernizing and progressive on race. This new kind replaced the fading kind – conservatively populist, segregationist, sometimes irascible and demagogic and often, but not always, anti-intellectual.

The decade changed the state as surely and substantially as the newly in-charge Republicans are changing it now – more, actually, since the Republicans are just getting started.

Consider this timeline:

1970: The governor entering the decade is a transplanted and liberal New York Republican multi-millionaire, Winthrop Rockefeller. He seeks to enlighten the state on race and to modernize its politics from the segregationist and machine era of Orval Faubus. But the state Legislature, almost exclusively Democratic and resentful of the threat that Rockefeller’s money posed to their re-elections, resists.

He does manage to get enacted a law permitting mixed drinks by local option in wet counties, which will allow state government to be graced in the early ‘70s with a new and important gathering place – T.G.I.Friday’s at Markham and Victory, a block or so from the legislative chambers. Happy hour fun will be had there. Political relationships will be formed there. New-age policies will be advanced there.

The state considers and eventually rejects a new state constitution that had been drafted by a constitutional convention the year before at Rockefeller’s behest.

BUMPERS WINS HANDILY

The charismatic and oratorically gifted Bumpers, who’d gone to law school at Northwestern, rises from near-universal anonymity as a small-town lawyer in Charleston. He announces for governor in June, and, three months later, wins the Democratic nomination. Then he wins the governorship two months after that. It’s safe to say there is no more politically transformative five-month period in the state’s history than this June-to-November romance of Bumpers and Arkansas.

The 44-year-old Bumpers came from the West Arkansas legal community, where he was admired for his courtroom skill, and the statewide organization of young and rising community leaders called the Jaycees, for Junior Chamber of Commerce.

Saying his father had taught him that public service was a noble profession, and refusing stubbornly to criticize his opponents even when people told him they wouldn’t support him unless he did, Bumpers, a new kind of Democrat, doesn’t merely defeat both Faubus and Rockefeller. He routs them. He launches an era that won’t fully end until a child of it, Mike Beebe, is term-limited as governor in 2014 and replaced by Republican Asa Hutchinson.

1972: David Pryor, a 38-year-old congressman who had been an anti-Faubus reformer and so-called “Young Turk” from election as a state representative from Camden at the age of 25 in 1960, mounts a bold Democratic primary challenge to the veteran U.S. Senate fixture and legendary appropriator, John McClellan, then 76. Pryor seems to have McClellan on the ropes until, in a televised debate during a runoff, McClellan scoffs at Pryor’s reference to campaign funds he’s received from regular folks dipping into their cookie jars. McClellan, the ailing and fading old pol with a prosecutor’s style, rallies himself to hammer the young challenger with a bass-voiced enumeration of big out-of-state labor contributions Pryor has received. McClellan wins the runoff, 52-48. Pryor learns lessons. He’ll be back.

1973: Bumpers appoints to the Arkansas State University Board of Trustees, effective in 1974, a young man not long graduated from that college, a 27-year-old Searcy lawyer named Beebe. Bumpers gets talked into the appointment by his nephew and trusted executive secretary, 26-year-old Archie Schaffer, a medical school dropout who had befriended Beebe at A-State, where Beebe had been his pledge trainer.

1974: Bumpers challenges U.S. Sen. J. William Fulbright in the Democratic primary, and drubs the world-respected opponent of the Vietnam War. Pryor gets elected governor, defeating, among others, Faubus.

CLINTON’S FIRST RUN

A 27-year-old Northwest Arkansas phenomenon by the name of Bill Clinton – just back to his home state from working in the George McGovern campaign in Texas, and now teaching law at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville – challenges Republican U.S. Rep. John Paul Hammerschmidt in the Republican hills. Because of Clinton’s uncommon political talent and a post-Watergate backlash against incumbency and Republicans, Clinton gets to 47 percent in a loss that amounted to a win in that it propelled him along a road to world history.

On the campaign trail, Bumpers meets the young Clinton, who had worked for Fulbright and who tells Bumpers he can’t support him in his challenge to such a great senator. Bumpers tells Clinton that if he ever became vulnerable to defeat by an undesirable opponent, he hoped young Clinton would run against him to keep the seat from going to an undesirable challenger.

“Man, he’s good,” Clinton recalled thinking of Bumpers on that occasion when he eulogized the departed senator a few weeks ago. As it happened, Clinton would consider running against Bumpers in 1986, when Bumpers would defeat a young Republican lawyer named Asa Hutchinson.

That aforementioned Bumpers-Clinton conversation actually takes place at a traditional primary-season rally in Russellville sponsored by the Pope County Democratic Women. The late U.S. Senator Robert Byrd of West Virginia appears there and plays the fiddle to support his friend Fulbright against this presumptuous challenge from Bumpers. Eventually, years later, Sens. Bumpers and Byrd would make their peace.

1975: Hillary Rodham, from suburban Chicago and Yale Law School and staff work for the House Judiciary Committee that returned articles of impeachment against Richard Nixon, marries Clinton in Fayetteville, joins the UA Law School faculty and becomes an unlikely Arkansan.

Pryor, as governor, pushes a radical plan to reduce the state tax base and permit local home-rule taxation by city and county governments. The Legislature rejects the plan and dilutes it beyond recognition, largely because education forces don’t want to lose the state money and because local government officials don’t want to be at the mercy of tax enactments at home. Famously, Pryor says his plan will allow local people to decide whether they want to pay a tax or buy a coon dog. Thus his ill-fated initiative becomes known, mostly derisively, as the “coon dog” plan.

Meantime, Pryor, long possessed of a reform-minded interest in a new state constitution, pushes for a “limited constitutional convention” that the voters would not be required to call by election and which would be restricted to a consideration of revisions in a few articles. By 4-to-3, the Arkansas Supreme Court says he can’t legally avoid an election and limit the agenda pre-emptively in that way.

1976: Clinton gets elected attorney general and heads the Jimmy Carter presidential campaign in the state. Carter carries Arkansas by 65-35. Only his home state, Georgia, gives him a better vote, at 66-34. Plainly, the ‘70s in Arkansas belong to Democrats.

A RARE SENATE OPENING

1978: Because of McClellan’s death at 81, a rare U.S. Senate opening exists, and three of the state’s most prominent rising Democrats – Pryor, U.S. Rep. Jim Guy Tucker and U.S. Rep. Ray Thornton, the latter having voted for the articles of impeachment of Richard Nixon as a member of the House Judiciary Committee – wage an epic battle in the primary. Absent issue differences among these like-thinking and new-generation moderate Democrats, the race is a personality contest – a split personality context, you might say. Bumpers’ nephew and former top aide, Schaffer, manages Thornton’s campaign.

You will notice that the decade’s big races were Democratic primaries arising from simple opportunities, not so much from issues or philosophical differences.

By rounded numbers, leaving off the decimal points: Pryor gets 34 percent, Tucker 33 and Thornton 32. Pryor wins the runoff over Tucker, 54-46. Meantime, Clinton, at 32, gets elected the nation’s youngest governor. In fact, the state elects the nation’s youngest attorney general, in Steve Clark, and youngest secretary of state, in Paul Riviere – both Democrats, of course.

1980, marking the decade’s end: The state has another convention to write a new Constitution, this time at the reform initiative of Pryor as governor. This proposed constitution gets rejected by voters, probably because of the conservative mood of the Ronald Reagan national landslide as well as concern, as in 1970, about making it easier for state and local governments to raise taxes. That makes three failed attempts at a new state constitution in the decade. The state hasn’t tried since.

Oh, and by the way: Clinton gets beat for re-election as governor by Republican Frank White in an epic upset that Clinton would reverse in 1982.

The takeaway from that timeline is that Arkansans with an interest in politics should have had to buy tickets to the 1970s.

PRYOR ON THOSE TIMES

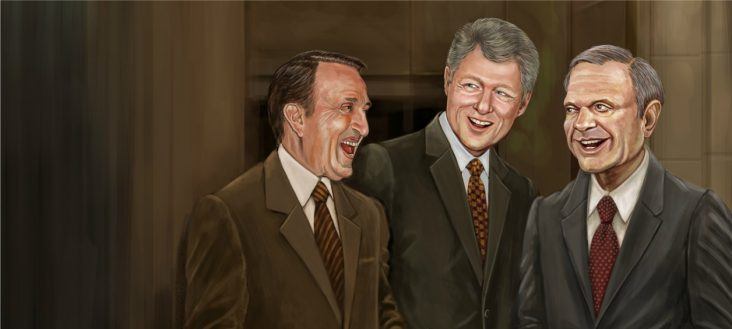

Clearly there are three main characters in this ‘70s Arkansas political saga – Bumpers, Pryor and Clinton. The one among them actually making the most appearances in the timeline is, at 81, still spry and sharp and ever-willing to chat about the old days.

Pryor reminisced recently at a conference table in an elegantly restored home on Izard Street that he shares as an office with his wife and son, the former U.S. Sen. Mark Pryor, a victim of the new Republican era.

The Pryors have decorated the office’s walls as a veritable museum of Arkansas political history, and the first order of business for any visit is Pryor’s “two-minute tour,” which lasts longer.

Pryor said Arkansas in the 1970s was still putting its primary premium on “retail politics,” meaning the personal kind encompassing old-fashioned glad-handing and stump-speaking. He retrieved a photograph of Bumpers giving a stump speech with Pryor beside him – astride a donkey. Television, much less the obsession on big money for advertising in the Citizens United era that Pryor now laments with near-anguish, wasn’t yet the main element of the game. “Think about it,” Pryor said. “The first case of a televised debate making a difference wasn’t until 1960 with Kennedy and Nixon.”

And think about something else: The first case of a televised debate making a difference in Arkansas politics wasn’t until 1972 with Pryor and McClellan. The effect wasn’t good for Pryor.

Retail politics still dominated, but that Sunday evening televised debate was a seismic occasion.

Pryor recalled it this way: He came back to Little Rock on a late Saturday afternoon in June from the Pink Tomato Festival, long a mandatory retail-politics appearance until, by way of introducing a new era, Tom Cotton blew it off last year to attend a Koch brothers’ retreat in California, and won big anyway. The televised debate would be Sunday night.

Pryor had not yet prepped a whit for the debate. There had been no cram sessions with aides on policy or debate style. There had been no rehearsals with a stand-in for McClellan.

A single aide and advisor, his trusted friend Don Harrell, went with Pryor to a room at Howard Johnson’s on South University that Saturday evening for a little privacy to get ready for the event only 24 hours away.

“My strategic error,” Pryor recalled, “was that I decided I needed to appear respectful and even deferential to the veteran senator.”

That’s understandable. Just two years before, Bumpers had blazed from that 1 percent name recognition in June to an early-September runoff routing of Faubus by running a famously “positive campaign.” Schaffer remembers that one of the first persons to walk into the Bumpers headquarters the morning after he squeezed into a runoff against Faubus was the late liberal lioness of Little Rock, Brownie Ledbetter. She had previously told Bumpers that she would not support him in the eight-man primary unless he attacked the machine politics and record of Faubus. Bumpers simply would not do it, and, in time, his smile-and-shoeshine campaign would offer Ledbetter and other reformers their only – and best – Democratic option.

But one thing about Arkansas politics in the 1970s or any other time is that it will defy consistency and contradict itself. What worked for Bumpers didn’t work for Pryor.

THAT ‘COOKIE JARS’ LINE

“What I came to realize,” Pryor said, “is that, when people tune in to a televised political debate, it’s like going to a prize fight. They’re not looking for two guys to dance around. They want blood on the canvas.”

They got some, and it was young David’s.

“At some point during my preparations with Don,” Pryor recalled, “we decided it would be good for me to say, if the opportunity arose, that my support came from people around the state dipping into their cookie jars.”

So Pryor said it. And suddenly the gruff old incumbent senator got young again.

McClellan responded: Cookie jars? How about this national union and another one, and another, and another? McClellan relentlessly ran through the names of powerful unions sending money to use this pliable and ambitious young man to try to take out a senator who’d fought their corruption. These weren’t hard-working Arkansas people scraping the bottoms of their cookie jars. These were big, bad, alien forces.

The truth was that Pryor didn’t have a particularly compelling reason to make the race against McClellan. His “Young Turk” reform fight had been more state-based against Faubus than nationally based against McClellan.

The fact, he said, was that, in six years as a congressman representing southern Arkansas, “I was bored to death.”

Pryor said he’d asked a staff member to estimate how long it would take him to rise from his membership on the House Appropriations Committee to the chairmanship. The best estimate was 35 years. That was not how he wanted to spend his political life.

Beyond that, Pryor said, he had pretty much alienated himself from any help for his career from the Southern Democratic political establishment in Washington. He’d done that in 1968 by voting to seat the black delegation from Mississippi at the national convention.

One thing you’ll consistently be reminded of when considering Pryor’s history is that, notwithstanding his eventual reputation for an aw-shucks finesse of tough issues, he came up early as one of the state’s bravest and brashest liberal reformers.

Pryor would bounce immediately back from his narrow loss to McClellan to get elected governor in 1974, as Bumpers defeated Fulbright for the U.S. Senate. Bumpers did it again with the decidedly positive campaign that wouldn’t work for Pryor against McClellan.

Bumpers was not critical in his lone televised debate with Fulbright, which was aired nationally as a “joint appearance” on a Sunday news show on ABC called “Issues and Answers.” The national interest was owing to Fulbright’s prominence in foreign policy and Bumpers’ rising status. At one point during the program Fulbright exasperatedly told the moderator, “You’re seeing how hard it is to get this man to answer a question.”

Indeed, Bumpers had once been asked at a news conference as governor how he would respond to the charge that he was wishy-washy on the issues. And Bumpers said, “Maybe I am and maybe I’m not.”

RATING THE GOVERNORS

Through it all, the steady theme of the ‘70s in Arkansas was reform, moderation, modernizing and racial progress.

Arkansas historians and political scientists have rated Bumpers the state’s best governor of the 20th Century, which, in effect, means greatest ever. He raised income taxes, reorganized state government, created community colleges and advanced free textbooks and universal childhood immunization. And he did it as an absolute political novice with, as his key executive aide, that 23-year-old nephew, Schaffer, who modestly credits whatever success he had to his ability to negotiate happy hour at T.G.I. Friday’s. But Bumpers had some other uncommonly strong staff help, including that of the late Brad Jesson, his beloved friend and Fort Smith lawyer who, poignantly, died during Bumpers’ funeral in Charleston.

Bumpers had first wanted Jesson as his executive secretary. But Jesson couldn’t afford to leave his law practice full-time. He did agree, though, to come to Little Rock during legislative sessions to head the liaisons whipping the Legislature for Bumpers’ agenda.

Bumpers also had on that legislative team an uncommonly cerebral young lawyer named Richard Arnold, whom Clinton still laments not being able to nominate to the U.S. Supreme Court. That was owing to Arnold’s health and concern that Republicans might get to fill the seat before any legacy could be realized.

Clinton was rated third and Rockefeller fourth among Arkansas governors of the 20th Century – Clinton for education reforms, mainly in the early ’80s, and Rockefeller for his transitional value in the late ’60s in defeating Faubus and advancing a strong reform agenda that Bumpers would later get enacted.

Still, the fact remains that three of the top-rated governors of Arkansas in the 20th Century served in one decade, this greatest decade, the 1970s. The other, second-ranked George Donaghey, served from 1909 to 1913 and advanced the creation of public colleges and a system of public health regulation.

THE ARKANSAS PLAN

Missing among those highest-rated governors is that fourth progressive chief executive of the ‘70s – Pryor, the earliest reformer whose governorship from 1975 to 1979 was not as eventful or transformative. Nor was it as favored with historic opportunity and money as Bumpers’. And it was not as dramatic or marked by fateful political ambition as Clinton’s.

“So we did more symbolic things, I guess you could say,” Pryor said.

He couldn’t get constitutional reform done. And what became the central policy initiative of his four-year governorship, the home-rule Arkansas Plan, was . . . well, let’s allow Pryor himself to assess it: “Some days I think it was radical and some days I think it may have been pretty smart,” but, as to the question of whether he’d do it again, “no, I don’t think so.”

Pryor recalled sitting down with his smartest aides to brief his best legislative ally, the late and colorful and homespun state Rep. Lloyd George of Danville, on the Arkansas Plan. Pryor said it probably was telling that, after the explanation, the farmer George declared, “I don’t understand a word of it, but I’m all for it.”

The failure of that policy aside, there may have been broader significance – indeed a microcosm – in that humorous moment.

What happened generally in Arkansas politics and government in the ‘70s is that moderate, modernizing, new-generation governors possessed of uncommon political and personal skills – Bumpers, Pryor and Clinton – melded with enough of the crazy-like-a-fox good ol’ boys from the hinterlands to move a backwater place forward.

The effect was to distance the state from the school integration disgrace of 1957 and transform it to a place that could produce in 1992 a president of the United States.

You could say, as someone did, that Bumpers was preceded in death by the Arkansas political era he launched – by 14 months, the time between the completion of the Republican takeover in November 2014 and his death in January 2016.

The new era pales in comparison in terms of personality and drama and eventfulness, but is young yet.